This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Thirty years ago, the deployment of US cruise and Pershing missiles began in western Europe.

A total of 572 new medium-range missiles were planned, of which 160 would go to Britain, intended for Greenham Common in Berkshire and Molesworth in Cambridgeshire.

The deployment marked a major shift in US policy following its defeat in Vietnam.

Unable to intervene against a number of successful Soviet-backed national liberation struggles because US public opinion was stricken with "Vietnam syndrome" - they didn't want any more US soldiers coming home in body bags - Washington decided to weaken the Soviet Union instead by launching a massive new nuclear arms race that it would not be able to afford.

The decision for Britain to take the missiles was made in January 1979 - without parliamentary consultation - by Labour prime minister Jim Callaghan.

West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt also agreed to take the US missiles, as eventually did Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium.

The decision was made public in December 1979, by which time Margaret Thatcher was in power.

The anti-missiles movement that arose as a result was the greatest wave of protest that had taken place in western Europe since World War II.

During the first years of the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of people mobilised across these countries to try to prevent the siting of the missiles.

And the peace movement had strong support. Across the five countries that would receive the new missiles, approval of the peace movement ranged between 55 and 81 per cent.

The driving force for this popular support was straightforward. It became clear that a "limited nuclear war" was being envisaged, to take place in Europe, to avoid the superpowers attacking each other with long-range missiles.

Western and eastern Europe and the European parts of the Soviet Union would be the battleground.

Not surprisingly, this produced a reaction of extreme alarm.

For the peace movement, the advance notice of the deployment of the missiles was a real challenge.

It presented the opportunity to build so great an opposition that the governments would be forced to change their minds. But the political context was unfavourable.

New US president Reagan designated the Soviet Union "the evil empire" and pledged to lead the free world in its struggle against communism. Of course he found a willing ally in Margaret Thatcher.

Together they redefined conservative politics into a militant crusade to impose their version of free-market politics and democracy.

Nevertheless, public concern about the threat of nuclear weapons was rising.

Even by April 1980, an opinion poll showed that over 40 per cent thought that a nuclear war was likely within 10 years.

And that concern was expressed through the growth of the movement - anti-missiles groups sprang up across the country.

CND national membership grew from 4,267 in 1979 to 90,000 in 1984 and its local membership grew to 250,000. Demonstrations attracted hundreds of thousands and peace camps sprang up at bases, involving tens of thousands.

But the block to success was a political one. In 1983, the Conservatives were again elected, even though there were clear majorities in opinion polls against cruise.

The key factor in the defeat of Labour - which was anti-nuclear under the leadership of Michael Foot - was the split of the Social Democratic Party from Labour.

This succeeded in massively cutting the Labour vote and splitting the opposition to the Tories.

Although the Conservative vote fell and it was outpolled by Labour and the SDP, the Tories won the election.

In November 1983, the deployment of cruise and Pershing missiles in western Europe set in train and the British government began to take a harder line against those protesting at the bases.

That same month, defence secretary Michael Heseltine told Parliament that protesters who got too near the missiles would be shot.

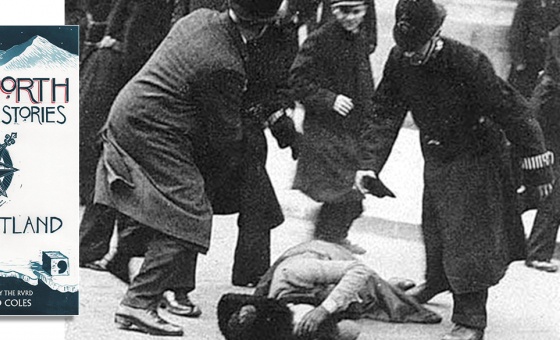

None were shot, but they were treated with increasing brutality by the police.

In April 1984 the police attempted to close down the camp at Greenham Common, tearing down the shelters and making numerous arrests. But the women came back and remained there until ultimately the missiles were removed.

In February 1985, 3,000 soldiers and police arrived at Molesworth in the middle of the night to evict around a hundred, mostly Quaker, peace activists.

But in spite of the missiles arriving, the sustained nature of the anti-missile protest was taking its toll politically. Pressure mounted on the US from governments in western Europe who were feeling the squeeze from their electors over fears of the arms race and the possibility of nuclear war.

Reagan was also under pressure domestically to make some move towards peace as he would be hard-pressed by the Democrats on this issue in the forthcoming presidential election.

The US and the Soviet Union went back to the negotiating table in 1985, and within two years, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty had been signed by Reagan and Gorbachov.

Soon after, the missiles were removed and destroyed and the base at Greenham Common was dismantled.

When the missiles arrived in 1983, we had no idea that they would be so short-lived.

We felt we had lost the fight - but in fact we had helped force a significant shift in policy internationally, the implications of which unfolded within just a few years.

The parallel with recent struggles is striking. We failed to stop the war on Iraq in 2003, but the scale of our protest ultimately shifted political attitudes to the extent that Parliament refused to attack Syria in August 2013.

Much has changed as a result. As we seek now to scrap Trident and secure the global abolition of nuclear weapons, we should understand that we, through our campaigning work, can shape the outcome.

We may not know which will be the last straw that will break nuclear weapons forever, but there will be one.

And it may be the result of our action. We must never underestimate the power of protest and its political impact.

Kate Hudson is general secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.