This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

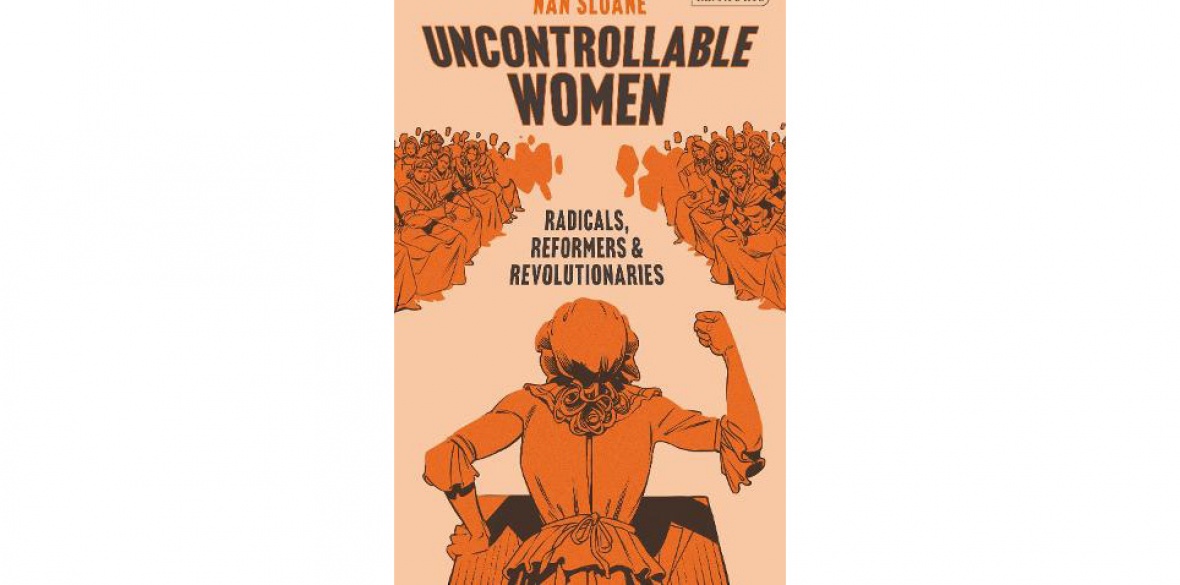

Uncontrollable Women: Radicals, Reformers & Revolutionaries.

by Nan Sloane

IB Tauris £17.46

THE publishing world seems to have suddenly discovered “invisible women” and resolved to champion trailblazers to whom our society owes a long overdue debt.

The concept of “herstory” has been around for a while, coined by some feminist researchers and authors criticising male domination in “his story.” It’s a wry joke, of course; writers do understand the neologism. But the challenge is well founded. Where have these wonderful women been, all our lives?

Nan Sloane has done a grand job here. Producing non-fiction, which also moves along with a graceful narrative arc, is tricky enough. Unearthing these neglected lives demands meticulous research. Writing a page-turner calls for a storyteller’s skill.

The period covered takes us from 1789 to 1832. History buffs (and pub quizzers) will be shouting “French Revolution” and “Great Reform Act.” Yes — not that long an era, but certainly one replete with social upheaval. Sheila Rowbotham’s seminal (shouldn’t that be “ovular”?) work Hidden from History might have studied 300 years of women’s oppression, but Sloane has made an excellent choice in looking at these 40-odd years.

In her introduction, she says: “….the ‘popular’ history of women tends to be restricted to royalty, the suffrage movement and Florence Nightingale, with a few nods to philanthropists such as Elizabeth Fry.”

Sloane points to the heavy focus on women’s fight for the vote as leading to the view that “….women had no political presence at all before the 1860s.” And she criticises “…the rather questionable habit of describing every female activist as feminist regardless of whether or not she actually was.”

Some of her choices fought for different freedoms, rather than suffrage — Anna Laetitia Barbauld for an end to religious discrimination, Mary Fildes for parliamentary reform, and Susannah Wright for the separation of church and state.

As France became the first country in Europe to legalise divorce on demand for both men and women, in 1792, a group of working-class men met in London. The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was to be outlawed by 1799, but it produced pamphlets and books, ran debates and lobbied for reform. It never admitted women.

Says Sloane: “Radical men could certainly be supportive, but often it was more because they wanted backing and help from women than because they had any profound belief in sexuality equality.”

“Plus ca change, plus ca la meme chose,” as Karr said in 1849 — and women have been saying ever since ...

It’s clear from the start that there are some gems in this work, as well as some perceptive connections with the current day. Chapter One looks at Mary Wollstonecraft — not “hidden from history” per se — and there’s a delightful reminder that the Edinburgh Review was convinced that she was a he. With obvious irritation, they said they’d have reviewed Vindication of the Rights of Men differently, had they known the author’s sex!

There’s an effective tactic Sloane employs, with an end-of-chapter cliffhanger. Here, Wollstonecraft sets off for France, alone, and we’re told: “Tucked safely into her bag she carried with her several letters of introduction, one ... to the famous author Helen Maria Williams, one of the most remarkable women of the age.”

And we’re off, to the second chapter, celebrating a woman about whom I’d known next to nothing. Williams was a reporter, and held parties at which conversation was always “deeply political and overhung by an air of excitement, danger and possibility.” Sloane says she “understood the sense of sisterhood that arose amongst women at times of crisis,” and that she “saw women as having political agency regardless of their status, and observed and celebrated their exercise of it.”

Imprisoned in Paris during the Reign of Terror, Williams used her time in writing sonnets, and continued translating French literature to English. She was vilified by the British press, and Horace Walpole called her a “scribbling trollope.”

In contrast to Williams’s literary life, there’s the story of illiterate Jane Cousins. It seems possible that her husband John Carlile taught her to write; she was 30 when they married. He was to become a radical journalist and publisher, later jailed for blasphemous libel, leaving Jane alone and pregnant in a dilapidated flat above their Fleet Street bookshop.

She took on the business, paying fines and clearing their debts. She too was charged with seditious libel, appeared at court, with a defence speech clearly written by her husband. Found guilty, she was imprisoned for two years. Carlile later took up with a woman 20 years her junior.

Some books sit neatly in the reference section, others are picked up and read intermittently — those which are found one day by the armchair and another, on the bedside table. This one deserves to be kept close at hand, not only because it’s a damn good read, but because it’s a reminder of how strong women can be rendered invisible and silent, unless we shine a spotlight and amplify their voices. And — although I’d never encourage any reader to biblioclasm — on encountering a man who does nothing to fight for women’s sex-based rights, you could always hurl it at him.

LYNNE WALSH