This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

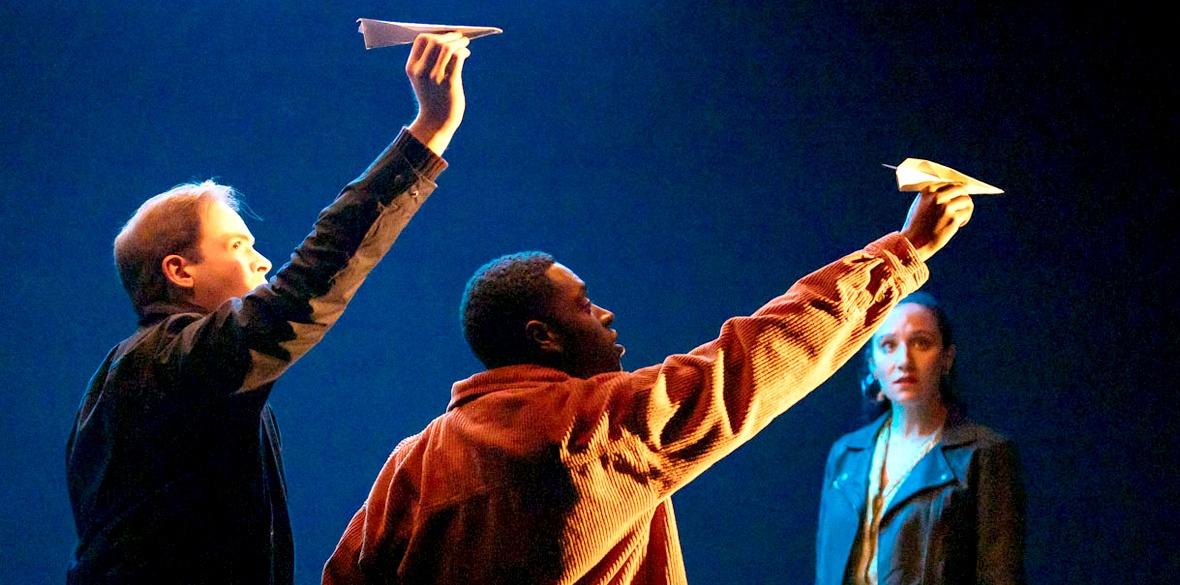

The Winston Machine

New Diorama Theatre, London

A ONE-ACT play commissioned from the Kandinsky theatre company, The Winston Machine examines how WWII is, perhaps, ceasing to be a key reference point for many British people.

The inference from events that unfold on stage is that we ought to view this as a good thing: a liberating experience that will release us from some of the knots we’ve tied ourselves in over the past 75 years.

Without deprecating the conflict, or the people who took part in it, The Winston Machine suggests that it’s time to move on, and that we’d all benefit from a bit more forward thinking.

This we see in the form of Becky (Rachel-Leah Hosker), a twenty-something living in the here-and-now but somehow dwelling in the shadow of events and values of the past, including the heroic acts of her grandfather, who was a WWII pilot.

Trapped in a boring job and engaged to someone she’s not that excited about (Hamish Macdougall), Becky’s escape is to wallow nostalgically in the romantic aura of the war – until she stumbles across an old school friend (Nathaniel Christian) who offers a potential way out.

With each of the three actors playing various other characters across the generations and little in the way of costume differentiation, it’s sometimes difficult to keep track of who’s who and what’s what.

This is especially the case in the early stages, where the scene changes are organic and – to add to the potential confusion – the lines are interspersed, for some reason, with excerpts of social media chats that cross-cut the conversation.

While the set is sparse — a sloping stage with just an old radio and a few chairs – the dialogue is anything but, and although the three impressive players do a grand job of keeping on top of the rattling pace, sometimes it feels as if they’re surfing precariously on a wave of words.

Gradually, however, shape begins to emerge from the challengingly quickfire beginnings, and we start to understand that most of the characters are not only blunted in some way by the after-effects of war, but are also struggling to find the sharp purpose in life that conflict so easily provides.

Despite this, the play’s conclusion is a reasonably optimistic one, suggesting that as images of spitfires and Vera Lynn continue to fade from the collective memory, fresh horizons will open up, and that we can expect a societal dividend as a result.

Runs until February 19: newdiorama.com