This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

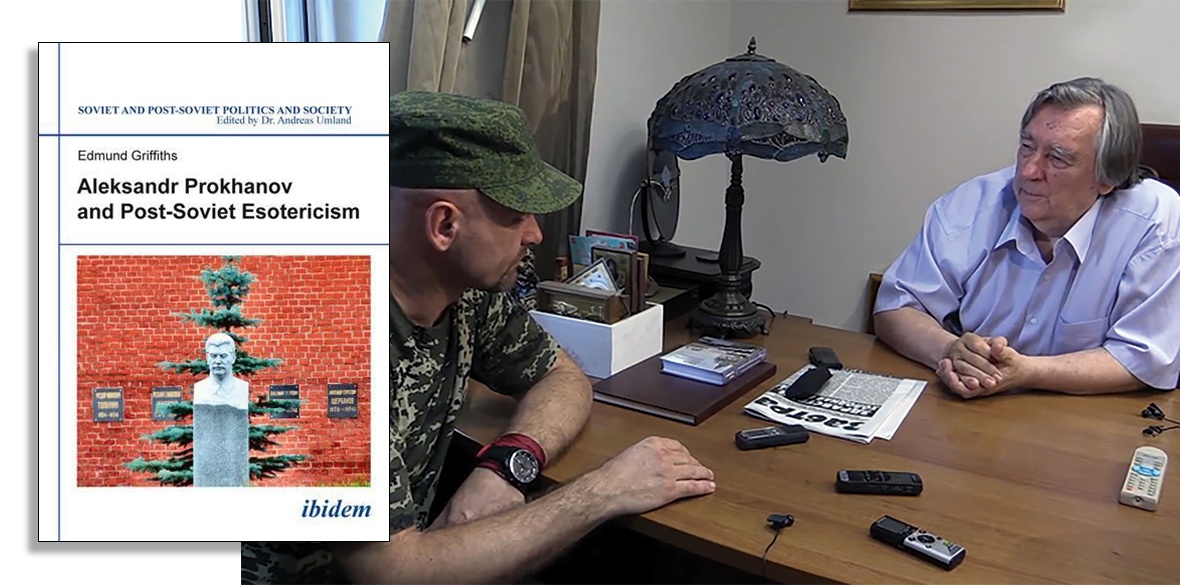

Aleksandr Prokhanov and Post-Soviet Esotericism

by Edmund Griffiths

Ibidem, £32

DON’T be put off by the title. Edmund Griffiths’s new study Aleksandr Prokhanov and Post-Soviet Esotericism sounds niche – but it is one of the most informative books you could read on modern Russian nationalism.

In Britain he’s unheard of. But Prokhanov is one of Russia’s best-selling novelists and longtime editor of the influential newspaper Zavtra (Tomorrow). He was also the reputed author of 1991’s A Word to the People – signed, among others, by the later Communist Party leader Gennady Zyuganov – the manifesto for that August’s failed coup against Mikhail Gorbachev, a last-ditch attempt to stop the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The “nightingale of the General Staff,” as he was known even in Soviet times for his devotion to the military, has been a formative influence on what was termed in the 1990s the “patriotic opposition” — a shifting alliance of everyone opposed to the politics of the Yeltsin years, ranging from orthodox communists to Orthodox priests.

If you’re one of those puzzled by the juxtaposition of Soviet and tsarist iconography on Russian demonstrations, you need to read this book: as Griffiths observes, when finding Stalin depicted on an ikon of the Virgin Mary no longer surprises us “we shall have gained a valuable perspective on Russia’s contemporary political culture”.

That culture was forged in the nightmare of the 1990s. Almost overnight Russia’s economy collapsed. Millions lost their savings and their jobs. Life expectancy plummeted. And Russians were “robbed of the future” — the promise of a coming communist era of plenty that generations had been brought up to work for was suddenly withdrawn.

Efforts to come to terms with this bring us to the “esotericism” of the title. For those who regretted the fall of the Soviet Union — which polls suggest was most people — the demise of the “good society” they had lost was troublingly self-inflicted.

Unlike some eastern European countries, there had not been any popular uprising against Soviet socialism in Russia. The state had been “overthrown, without any revolutionaries; stripped of its territories, without any victorious Allies”. Griffiths takes us on a tour of ancient Gnosticism to illuminate what happened next.

Religions have grappled with the “problem of evil”, how a benevolent deity can permit it to exist. Soviet nostalgics struggled with the problem of perestroika: how could a benevolent Soviet government cause its own collapse? Russia saw a mushrooming of conspiracy theories to explain it.

Griffiths rejects the term: what makes “conspiracy theories” distinctive is not conspiracy itself. It is esotericism: the notion that behind the apparent state of affairs there is a hidden truth.

As he has written elsewhere, these theories develop rapidly according to their own logic. A mundane proposition — that the moon landings were faked, say — morphs into a global conspiracy to explain how this truth has been covered up.

So the search for hidden truths about the collapse of the Soviet Union can end with novel takes on what the Soviet Union was in the first place, often imbued with mystic overtones. Themes of resurrecting the dead and colonising other planets (drawn from the 19th-century philosopher Nikolai Fedorov and pride in Soviet space technology) emerge as explanations of the true, hidden meaning of Soviet history.

A key figure in this reinterpretation is Stalin. Griffiths convincingly argues that Stalin’s unique prestige in modern Russia is the reaction to his vilification in the 1990s. If Stalin was for the Yeltsin establishment the symbol of all that was evil, those who hated it came to identify him with all that was good.

Yet the “second cult of Stalin” differs strikingly from his depiction in Soviet times. An example is the Russian protest chant “Here’s how we’ll complete the reforms: Stalin, Beria, Gulag!”

Traditional admirers of Stalin pointed to industrialisation, collectivisation or victory in World War II as the leader’s achievements. Association with secret police and labour camps is more common among Stalin critics. Here that is turned on its head, the repressive Stalin of Yeltsin-era narratives championed as a cry of rage against the new elite.

But that is only the start. Stalin in the hands of Russian nationalists can bear little resemblance to the historical Stalin. He becomes an incarnation of the “mysterious Maid of Eurasia,” among predecessors including Ivan the Terrible and Genghis Khan, a figure whose historic task was to restore imperial unity after a period of fragmentation and upheaval, and an Arthur-esque once and future king: “They say if you put your ear to the Volga steppe you can hear his footsteps. Perhaps Stalin is already among us... we repeat like an incantation, he is at hand, he is near, he will return”.

Stalin’s reinterpretation as a figure who, without changing the outer structures of the Soviet state, rebuilt Mother Russia from within it explains the appeal to the Putin-era Kremlin of what was once the “patriotic opposition”. Yeltsin’s hand-picked successor is presented likewise, a “gatherer of the Russian lands”, and has explicitly compared himself to Peter the Great in reclaiming territory for the motherland – in this case from Ukraine.

That’s partly why this is an important book. Prokhanov’s mysticism may be optional — though the aforementioned Stalin ikons do exist — but the broad thrust of his thinking, anti-liberalism, militarism, a belief in Russia’s imperial destiny, is shared by the Kremlin and to a degree the larger opposition parties. This study helps explain an ideology that cannot be ignored if Russian politics is to be understood.

But it is also a warning.

For all its utterly different presentation, Putin’s Russia is Yeltsin’s Russia, with its hyper-presidential political system, its unfair elections, its oligarchs and its rampant poverty. Widespread Soviet nostalgia has not brought back socialism or anything resembling it.

Collapsing living standards, corrupt, untrustworthy authorities, social catastrophe, can give birth to bizarre conspiracy theories and reactionary, dead-end politics. And all those factors are at play in Britain today.

Ben Chacko

Ben Chacko