This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Legacies: London Transport’s Caribbean Workforce

London Transport Museum, Covent Garden

WHEN London Transport had a recruitment problem in the late 1950s and early ’60s, it turned to the Caribbean to find bus conductors, Tube station staff, maintenance workers and canteen assistants.

The initial target was Barbados, though recruiting sergeants were later sent to Jamaica and Trinidad, as well as some of the smaller islands such as Grenada and Dominica. Around 6,000 people were directly signed up from the Caribbean between 1956 and 1970, and many more came over on their own account, taking up work on the Tubes and buses once they arrived.

Now a new exhibition at the London Transport Museum is celebrating the contribution those willing hands made to London life – while also looking at the bittersweet impact of emigration on their own existence.

Modest in scale but wide-ranging in scope, it takes a scrapbook approach to its subject, with an abundance of newspaper cuttings, posters, leaflets and photographs, as well as oral and video recordings that document the experiences of those involved.

While there’s a strong temptation for this kind of exhibition to focus on the headline-grabbing negatives – the trials of moving to a sometimes unwelcoming country, and the pernicious influence of racism – wisely its organisers (led by an advisory board of people of Caribbean heritage) have chosen to accentuate the more humdrum positives.

There is, of course, plenty about the things that surprised and disappointed new arrivals — including the funnelling of so many of them into unskilled jobs with limited prospects (“me come here fe drink milk, not fe milk cow,” says one contributor in an entertaining short film) and the terrible state of housing provision. “However poor you were in Barbados you weren’t used to sharing a room,” says former bus conductor Ruel Moseley in one recollection. “I cried like a baby the first week I was here.”

Some of the less obvious obstacles faced by new recruits are also highlighted – such as the fact that Caribbean territories dealt in cents and dollars on a decimal basis, whereas Britain was still on the old system of pounds, shillings and pence – a troublesome initial complication for those working as conductors, in ticket offices or the canteen.

There’s coverage, too, of the challenges associated with working in a huge city of which most new recruits knew next to nothing – meaning, for example, that they were often unable to be of much use when asked for directions, leading to accusations of unhelpfulness, or the observation that “if you were English you would know.”

On the whole, however, the focus tends more towards the heartwarming side of the immigration story – of new lives built, horizons expanded, support networks created, obstacles and prejudices overcome and friendships forged.

There’s a fascinating corner on the influence of the CRS Cardinals private members’ club, a hub of social activity for Caribbean LT employees with an all-conquering cricket team, and there’s mention, too, of the London Transport Caribbean Association, arranging outings and parties of the kind portrayed in a lovely photo of a group of day-tripping LT employees, arm in arm across the racial divide, on a visit to the seaside.

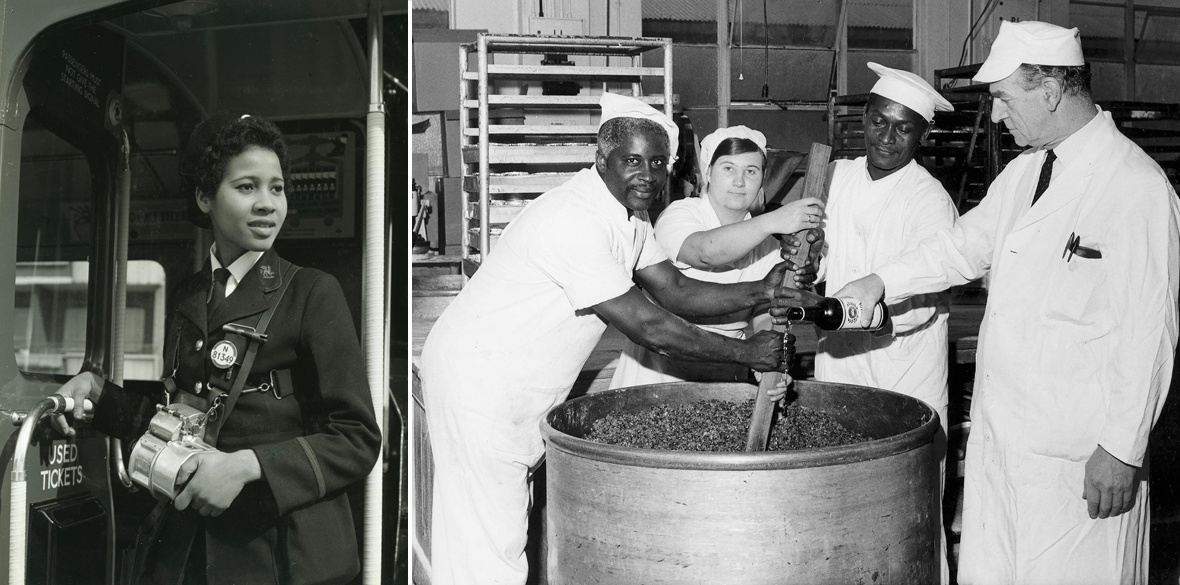

There are images from 1968 of female catering recruits receiving a lesson in pastry preparation, with observations on how Caribbean cooks introduced new flavours to the standard fare of LT canteens, and the story of Marva Braham, who came from Barbados in 1962, won the top cook competition in 1969 and was eventually promoted to be a general manager.

These and other intriguing snapshots build up a strong feel of what it was like to live and work in those now far-off times, when strong unionisation and an enlightened attitude from LT helped to support employees and nurture camaraderie.

They also help to suggest why the majority of recruits, at first expecting to spend no more than five years in London before returning home, decided to make the city their permanent base, some providing service to LT through two more family generations.

It’s heartening to feel that despite the damp, the cold, and the tribulations, so many found something to hold on to in their new workplace and environment – and, better still, that they were able to fashion their presence here into something of lasting value, both for themselves and for us all.

Free entrance with a ticket to the museum; runs until summer 2024: https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/visit/museum-guide/legacies-london-transports...