This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

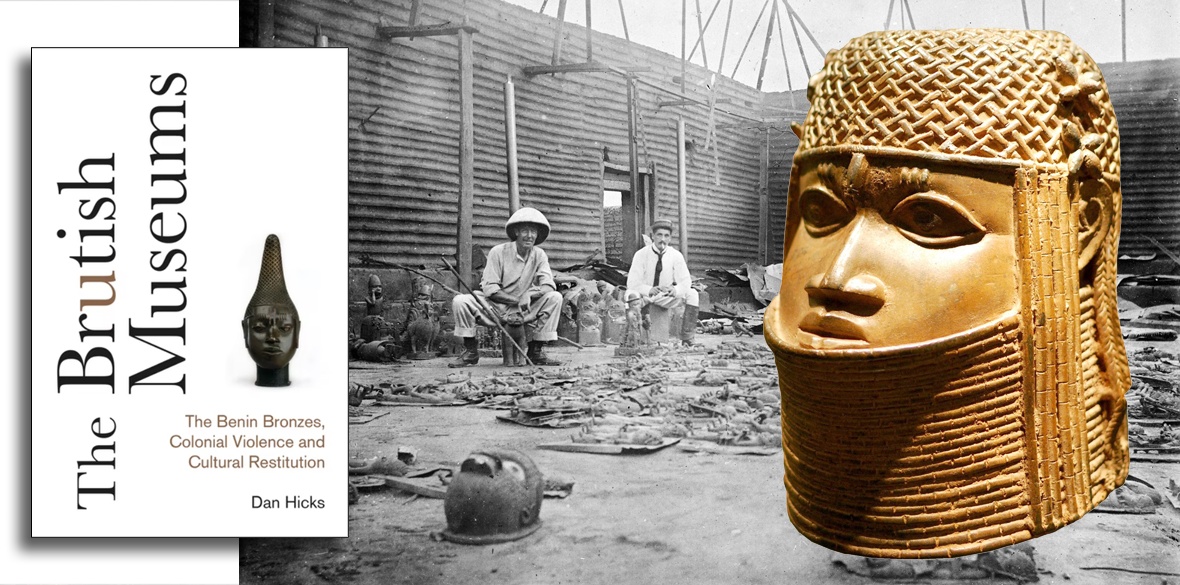

The Brutish Museums

by Dan Hicks

Pluto Press, £12.99

AMID the ongoing debate on colonial plunder, the role of museums and the return of cultural artefacts, Dan Hicks drops this passionately argued, explosive book into the mix.

Using the Benin Bronzes as the focus for his writing, he demolishes the arguments propounded by those museum directors who wish to maintain the status quo by retaining their looted treasures.

So-called punitive expeditions proliferated during the 19th century as European countries carved out empires, with the booty looted in the process found in every anthropological museum in the global North — 43 of the 154 museums holding Bronzes are in Britain and the British Museum alone has 192 pieces.

So as professor of contemporary archaeology at Oxford University and curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Hicks is at the centre of the discussion around the decolonisation of museums.

Received wisdom has it that the 1897 British attack on Benin City, resulting in total destruction, massacre and the plunder of about 10,000 artefacts, was a retaliation for the ambush of a party of British officials and traders.

However, Hicks shows that the sacking of the city was pre-planned long before this incident, and was not a punitive exercise but was part of a policy of regime change so Britain could control the lucrative trade in palm oil and rubber and lay claim to the land that would become Nigeria.

Hicks does not view the seizure of the Benin Bronzes as a single act of violent plunder, but as an ongoing trauma, revived each morning as museums open their doors to the public.

Again he attacks the perceived notion that the Bronzes were brought to Britain in an orderly way for safekeeping, when in fact they were grabbed in a chaotic fashion, with many sold on or disappearing forever into private hands, while others were used in museums to bolster the idea of British imperial greatness.

So not only does he sweep away all justifications for the looting of Benin, but also for the continued holding of Bronzes in museums across the global North.

Some museums have started to update information panels to show something of the true history of the acquisition of their collections, but Hicks argues this is simply not enough.

There is a need to offer an account of how and why the theft of objects occurred, to make museums anti-racist spaces and redefine them as sites of conscience where the violence of Britain’s role in Africa can be addressed.

Taking this to its logical conclusion, he advocates the return of artefacts to their rightful homes, so these nations can display them to celebrate and study their own heritage.

Nigeria has pushed for the restitution of its Bronzes for decades and in 2021 Jesus College Cambridge became the first British institution to return its Bronze, with Aberdeen University following suit.

Germany has agreed to return 1,100 artefacts which will be displayed in a new museum in Benin City.

Yet this policy has not resonated with many museums, notably the British Museum, which, as well as the rest of its global booty, holds four times more Bronzes than the rest of British museums put together.

Feeling the threat to its collection, the British Museum claims everything was obtained legally.

In 1981 it announced: “In the case of the Benin Bronzes the British were the legitimate authority in the land and therefore anything they did was in accordance with that legitimacy.”

During the 1980s the phrase “universal museum” came into play, claiming that Euro-American collections have become part of the heritage of the country that houses them, and to narrow the focus of collections is a disservice to visitors.

George Osborne, a trustee of the British Museum, reiterated the “universality” argument in 2021 to attack those who seek restitution of plundered artefacts.

He said, without a trace of irony, “Today there is no shortage of forces trying to divide us … the best response to this fragmenting society is to remind us of all that we share and of how our histories and cultures are all connected. We need to tell the story of our common humanity.”

Despite opposition, Hicks is optimistic that meaningful change will come to the management of anthropological museums; a time when nothing in their collections is there against the will of others.