This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

William Blake

Tate Britain

OFTEN linked to Constable and Turner as one of the three great British 19th-century Romantic artists, William Blake was a genuinely unique poet, printmaker and painter.

But, unlike them, he was never accepted by the art establishment of his day. He died a pauper at the age of 69 in 1827.

Despite a small middle-class following, he remained a social outsider due to his class, political radicalism and for being an artisan rather than a trained “fine artist” at a time when the art establishment, led by Joshua Reynolds, was redefining art as a liberal pursuit on a par with the gentlemanly intellectual pursuits of literature and philosophy.

Born in his parent’s Soho hosiery shop, Blake went to a local drawing school at the age of 10 and four years later he began a seven-year apprenticeship at the highly skilled and refined end of the printer’s trade under Basire, Engraver to the Society of Antiquaries.

There, Blake learned to draw from prints and plaster casts of the approved Old Masters and later from original sculptures in London’s churches and monuments.

When he subsequently enrolled in life drawing classes at the recently opened Royal Academy (RA) Schools, he was already an aesthetically aware 21-year-old master craftsman. Stifled by the RA’s rigid orthodoxies, he left after only a few months yet had absorbed the dominant aesthetic’s hierarchy of genres which was topped by history painting.

From then on, Blake earned a living as a highly skilled engraver while writing and painting in his spare time. Lacking the resources and patronage to paint in oils on large canvases as required by history painting, Blake worked mostly on paper on a small scale.

But he stubbornly stuck to history painting’s grand historical, literary, biblical and mythological subjects, through which he addressed philosophical, political and religious themes with very uneven results.

Without firm foundations in observational life drawing, his works often tend towards stereotypical representations of the human figure or to cramp subjects on surfaces too small to contain their complex, multi-layered themes.

Most of his early works of the 1780s are uninspiring — wishy-washy pastel or grey depictions of obscure Biblical narratives or of his own invented characters and mythologies, such as Tiriel Supporting the Dying Myrantana.

Stern, flowing-haired male sages gesticulate wildly and fey young women faint, supplicate or die gracefully. Occasional exceptions like Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing bring welcome lighthearted relief.

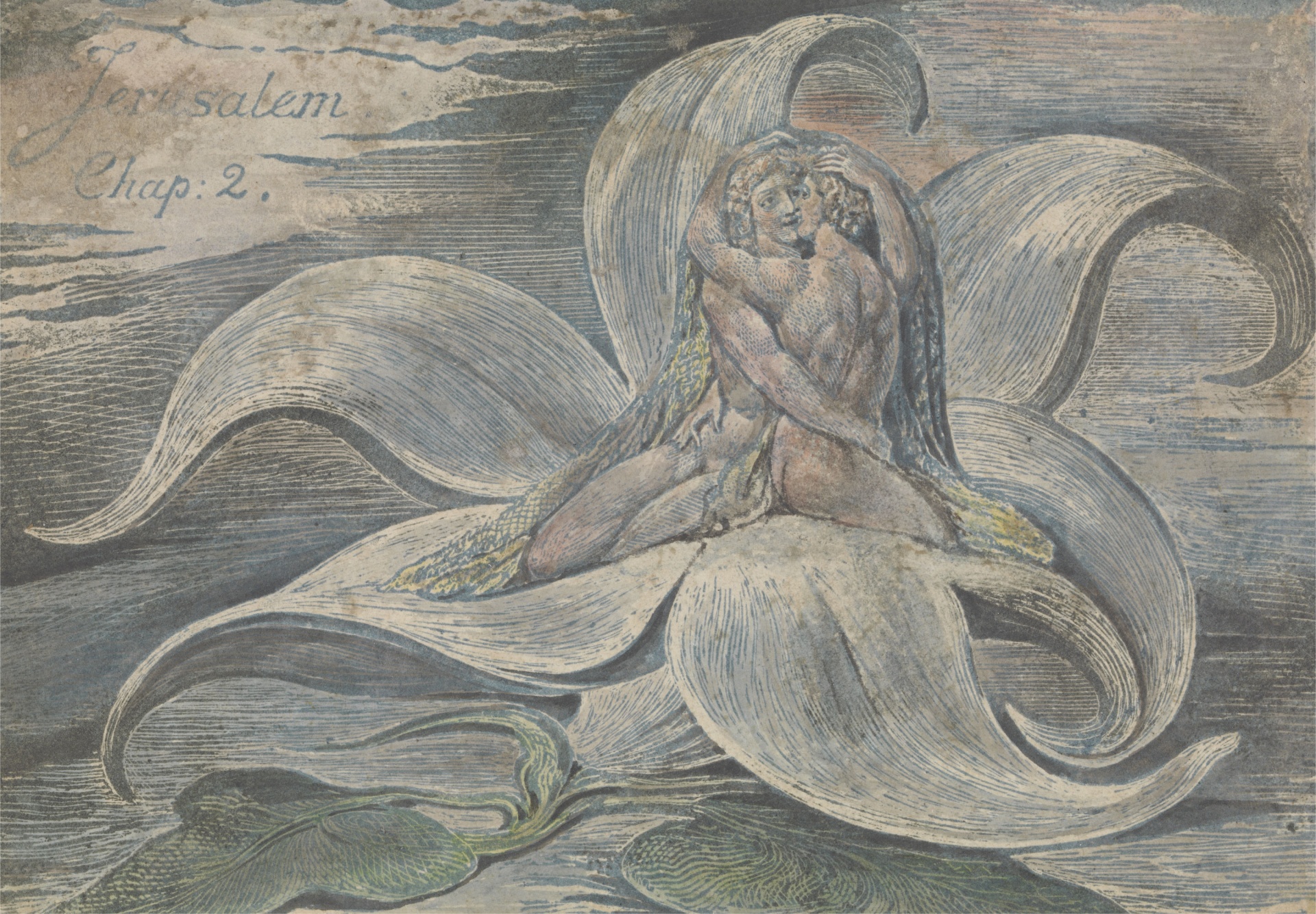

In the early 1790s, Blake joined other Jacobin craftsmen enthused by the ideals of the American and French revolutions. He produced several “prophetic books” merging images with tightly hand-written texts advocating liberty and decrying the despotic authority of church and state.

They included a few full-page coloured prints, one of the most successful being Albion Rose/Glad Day, in which a pale-skinned, golden-haired youth perches unevenly on a dark rocky slope, as if on top of the world against the darkness of the universe, as bands of optimistic oranges, yellows, lilacs and pinks burst like sunshine from his body.

His pose references the classical drawing Vitruvius Man but only his arms are outstretched symmetrically as he stands like a dancer, on one leg with the other stretched sideways. Calmly confident and seemingly sexually innocent, his lack of bodily shame and nakedness can be interpreted as epitomising classlessness, hope, liberty and equality.

The underlying and recurring themes in Blake’s images are the conflicting powers of good and evil, liberty and repression, despair and ecstasy, love and hate.

It is is heartening that the few memorable expressions of positive states of mind like Albion Rose are among his best-loved works but melodramatic expressions of sorrow, fear, hatred, cruelty and despair dominate.

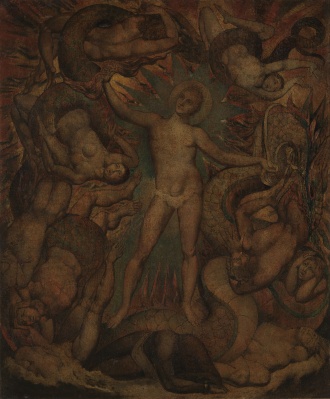

We see nightmarish monsters or wild-eyed people caged, crushed by pythons, attacked by snakes or consumed by fire, all redolent of adolescent obsessions with the monstrous.

Blake’s complex references are mostly too convoluted, ambiguous and obscured by his ideologically confused muddling of literary, biblical, patriotic, classical and his own mystical mythologies. Even Blake scholars can only speculate on, rather than provide definitive interpretations, of his works.

The artist was at his best when illustrating existing subjects, as in his late paintings which were prompted by an admiring group of young artists led by Samuel Palmer. By being grounded in the superbly disciplined narratives of Shakespeare, Dante and Milton, his over-fertile imagination blossomed without fading into fussy, unnecessary obscurities.

Tate Britain’s enthusiastic curators have produced a fascinating catalogue full of sociopolitical and cultural contexts but by focusing on Blake’s image-making they overrate him as a visual artist and, divorced from their texts, the images mostly lack clarity of meaning and purpose.

Blake fans will enjoy the exhibition, while others may find it too big, with a surfeit of small images and unfathomable content to wade through before stumbling across the odd gem.

Runs until February 2, box office: tate.org.uk