This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

AS INTERNATIONAL Working Women’s Day approaches, it feels timely to reflect upon the myriad ways in which the dissenting histories of women have been censored and obscured, with their commitment and profound contribution to radical social change omitted from our popular narratives of global struggle and erased over time.

Even in the most publicly accessible story of women’s activism, that of the women’s suffrage movement, so many voices have been lost or elided, edited out in order to create an acceptable version of this once incendiary campaign, a version that the capitalist patriarchy will tolerate — liberal, not militant, reformist, not revolutionary and overwhelmingly middle class.

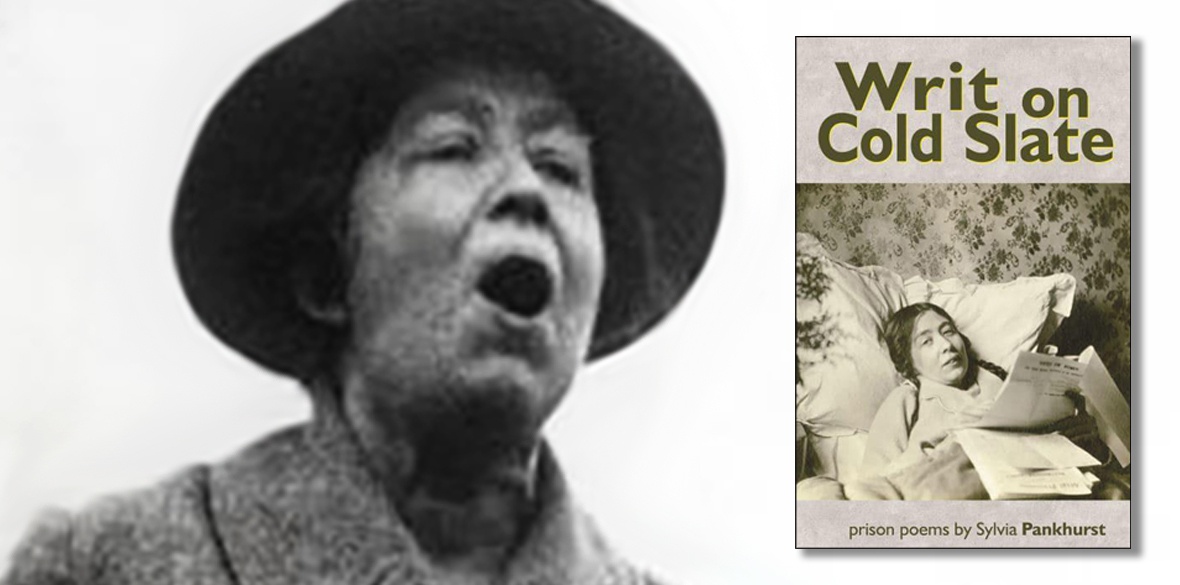

In the case of Writ on Cold Slate, just published by Smokestack Books, the long burial of Sylvia Pankhurst’s poetic voice demonstrates a loss not only to our militant feminist histories but also to literature. The story of its rediscovery and publication is a cause for both celebration and rage.

The Smokestack publication sees Pankhurst’s collection in print for the first time since 1922, when it was published in a very limited run via the revolutionary socialist newspaper the Workers’ Dreadnought.

A timely book, it brings Pankhurst’s poems together with photographs taken by Nora Smyth, a pioneering documentary photographer and a comrade of Pankhurst in the Women's Suffrage Federation (WSF). Both the photographs and the poems capture the dynamism, energy, and the sheer range of motivating concerns that mobilised the WSF in east London.

Particularly striking is the absolute embeddedness of the fight for women’s suffrage within the struggle for broader systemic social change. Pankhurst and the WSF were not single-issue campaigners, pleading for their right to representation in a society that oppressed and disenfranchised them. Rather, they sought to remake that society at a deep structural level, for the benefit of all.

Pankhurst worked tirelessly to implement these structural changes within her own community of Bow in east London, where the WSF established, among other initiatives, free mother and baby clinics, local nurseries, low-cost restaurants and free milk centres.

While Pankhurst’s heightened poetic language is not dissimilar to the work of Christina Rossetti, the scenes she describes are unflinchingly real. Pankhurst writes with an arresting mixture of lyric flair and social realism, so that clouds “flaunting their rounded splendour mid the blue” exist in fraught conjunction with “jangling keys” and “the sharp official tread” of prison life.

In Unto the Birds she seems to subvert prevailing poetic conventions about subjects fitting for the fairer sex, to describe how “sweet birdsong” to a prisoner serves only to “sharpen sorrow’s tooth.”

Throughout the collection, Pankhurst holds the persistently theorised frailty of women up against their brutalising treatment as prisoners. Aware that women’s relative “weakness,” both physically and mentally, were frequently enlisted as arguments for her continued subjugation, Pankhurst demonstrates time and again the dignity and endurance of female bodies and spirits.

Pankhurst herself endured, surviving nine periods of imprisonment and force-feeding between February and June 1914 as a result of the so-called Cat and Mouse Act whereby women on hunger strike, suffering from the effects of force-feeding, were released for long enough to recover, then immediately rearrested.

Writ on Cold Slate was itself composed in prison. The poem For Half a Year directly relates to Pankhurst’s six-month sentence for sedition, a sentence she received not agitating for women’s rights but for publishing articles in the Workers’ Dreadnought calling upon dockers to make common cause with the Soviet Union.

In For Half a Year her empathy extends to those suffering under colonial oppression abroad and to the miners and weavers at home. For Pankhurst, her own suffering is an instruction in solidarity and this is perhaps the most remarkable thing about these poems.

Sylvia Pankhurst’s own literary fate has proved metonymic for any struggle with working-class solidarity as its object. It serves the interests of those in power to focus attention on Pankhurst's mother and sister and on the activities of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), who were solely interested in gaining the vote for middle, upper-class, and property-owning women.

Pankhurst’s vibrant literary legacy champions the rights and conditions of poor and working women and attests to their active presence in the struggle for their own liberation as her comrades and co-prisoners.

It isn’t hopeless. We are not hopeless. It is important to hold onto this at a time when our government would like us to believe we are powerless. Keeping this in mind inoculates against apathy. No wonder no-one seemed very invested in bringing Pankhurst’s poems to wider attention.

The poems in Writ on Cold Slate transmit a sense of their deeply embedded social and political context, but they also remind us that we are capable of understanding, and indeed deserving, of more than we are given credit for. These poems do not patronise their working-class readers.

In the poem For Half a Year, the newly convicted speaker, about to descend the “narrow steps/unto a world of shades for half a year,” compares herself to Persephone entering Hades. It is an evocative poetic moment and a reminder of the systems that so brutalised women prisoners in Pankhurst’s day are with us still.

I do not doubt she would be writing and campaigning to dismantle such barbarous places. But she is not alive today and this task must fall to us in solidarity with all our sisters, wherever they are, wherever they are from.

Writ on Cold Slate, £7.99, is available from Smokestack Books, smokestack-books.co.uk. A fuller version of this article is available at Culture Matters, culturematters.org.uk