This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IT IS NOW 70 years since playwright Arthur Miller’s long-time artistic collaborator, Elia Kazan, appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and agreed to name names to save his own skin.

Miller and Kazan had been close friends throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, but after Kazan’s testimony to the HUAC in April 1952, their friendship ended.

After speaking with Kazan about his testimony, Miller travelled to Salem, Massachusetts, to research the witch trials of 1692. This resulted in his iconic play, The Crucible, which was a metaphor for the McCarthy witch-hunts against communists in the USA during the 1950s. He and Kazan did not speak to each other for the next 10 years.

Kazan defended his own actions in his film On The Waterfront (1954), in which a dockworker heroically testifies against a corrupt union boss. Miller responded by writing A View From The Bridge (1955), a play that has long been on higher curriculum in Scotland.

But how many students understand the politics, both personal and national?

In the play a longshoreman outs his co-workers but is motivated only by jealousy and greed. Miller sent the script to Kazan “only to let you know what I think of stool-pigeons.”

Miller, who died 17 years ago, February 10, was born into a secular Jewish family in Brooklyn New York. His family were soon to be plunged into poverty by the great depression. Those years of mass unemployment, rampant poverty, racism and corruption formed the backdrop to his early writing.

Like a whole number of alert and creative youngsters, he gravitated to the political left and was, for a time at least, a member of the Communist Party, remaining close to it for a number of years. Certainly close enough for him to have been harassed by the FBI and hauled before the HUAC, where he refused to “name names” and as a result was sentenced to imprisonment, blacklisted and his passport taken away.

Miller’s autobiography, Timebends, is the story of the US through the 20th century. In his plays, he probed the very essence of what it was to be American. For many, he and his work became symbolic for the conscience of the country. In his later years, he became a vociferous advocate of intellectual freedom on a global scale and campaigned for oppressed writers everywhere.

In his autobiography, he also reflects on his own life as a man of the Left but never a party political animal, more a lone wolf. While his reflections on Marxism and his disillusionment with the Soviet Union will not please everyone, they provoke vital debate.

No one, however, could deny his courageous and principled stand at all times.

His understanding of human frailty, particularly within an economic system that deforms us all, that promises the earth while robbing us of our basic humanity, is unparalleled. His plays, like Shakespeare’s, will resonate as long as capitalism continues to exist.

His description of Hollywood during the 1940s and 1950s as a corrupt propaganda machine run by Harvey Weinstein-like bosses is compelling. All films had to conform to the “America is great” mantra and all baddies had to be commies and Soviet agents.

After one of his film scripts about the Brooklyn docks was accepted as an ‘excellent piece of work’, he was then told to rewrite it so that the corrupt union bosses were depicted as Communists, something demanded by the FBI and the corrupt union bosses. He refused.

In his play, All my Sons, set during the war, he portrays a business man who, conspiring with inspection officers, sells defective aeroplane spare parts to the air force, raking in good profits, while young American men were sacrificing their lives at the front. “The country clutched corruption to its breast.” he writes.

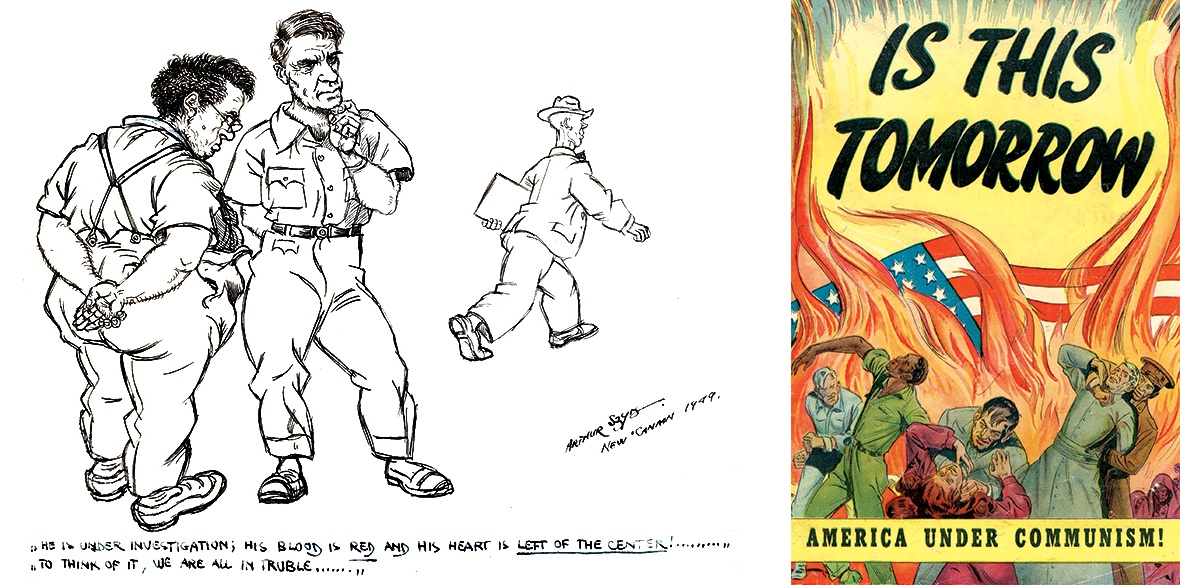

With the onset of the cold war, the US devolved rapidly into a proto-fascist country. The Soviet Union and communists were demonised, and any critique of the American way of life, however innocuous, was deemed highly subversive; spies and stool-pigeons were everywhere.

On campus professors spied on students who, in turn, denounced their teachers. The FBI trawled through everyone’s CVs. People were sacked at the drop of a hat if they had been seen on a May Day demonstration or had ever attended a peace meeting. Even those as diverse as Albert Einstein and Marilyn Monroe were spied upon and suspected of being clandestine communist agents.

Conformity was the over-riding demand and critical thinking itself became a subversive act.

It was a frightening time for anyone on the left, as Miller was. Many US intellectuals and artists, as well as trades unionists, during the 1930s and early 1940s were of the left, but within a few years almost all had been removed from the public arena, silenced, sacked and imprisoned.

“There was a prevailing paranoia,” Miller writes.

It is salutary to be reminded of that time, as most histories ignore it or gloss over it, and to realise how easy it can be to transform a nominally democratic country into a right-wing authoritarian one in such a short time.

The present book-bannings by a number of school boards in the US — including classics like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for instance — alongside the rise of far-right groups in a number of countries and media conformity in most Western countries all demonstrate that we are not immune from authoritarianism.