This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

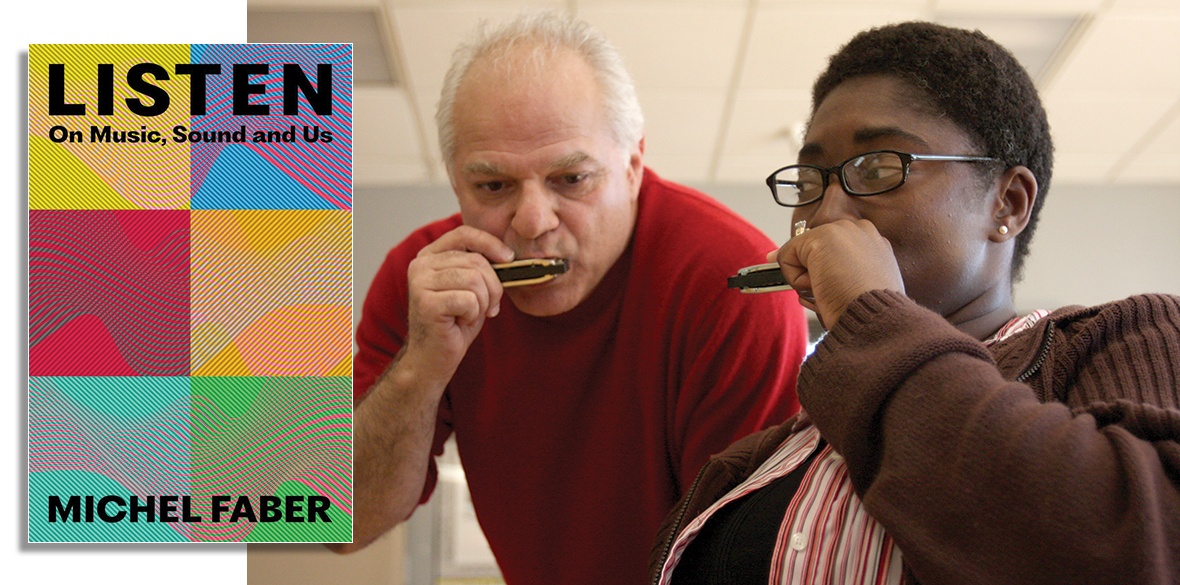

Listen (On Music, Sound and Us)

Michel Faber, Canongate, £20

MICHEL FABER has near-perfect recall of the lyrics and contributing musicians of Leo Sayer’s Just a Boy, an album he hasn’t listened to for 45 years. On the other hand, he forgets the names of outstanding artists he has heard more recently.

Listen is not a book of music criticism, nor does its author want to influence your taste. His focus is the psychology, sociology and phenomenology of our engagement with sound as a mode of expression.

Faber’s approach is digressive and exploratory. He visits a pre-school “Miniature Music Makers” session at a hipster cafe in Folkestone and recalls the soundtrack to his own unhappy childhood. He examines the emotional and aesthetic appeal – sometimes enduring, sometimes transient – of a range of artists and genres; and he considers the complex factors that determine musical taste.

Listen is fragmented and complex, and its sources are as varied as its themes. Faber draws on primary and secondary research – interviews, anecdotes, music journalism, recording industry data, biographies and social media. Despite its encyclopaedic scope and erudition it’s accessible and addictive.

One reason for this is the lively flow of the author’s ideas. There’s a particularly exhilarating chapter on the therapeutic value of music for people with head injuries, dementia and degenerative illnesses. It begins with a brief exploration of the neuropsychology of musical memories; it segues into a reflection on the extent to which our response to sound is reinforced by notions of identity and “cool”; and, finally, it considers the importance of personalised playlists where music is used in a clinical context. As Faber points out, being a teenager in the 1970s does not imply a nostalgic yearning for the sounds of Thin Lizzy or KC and the Sunshine Band.

Another factor in the book’s appeal is Faber’s prose style – clear, laconic and grounded in specific experience. Then there’s his acerbic wit. A riff on the “uniforms” of youth subcultures as symbols of identity and inclusion includes the couplet, “All the clonely people. Where do they all belong?”

Faber shares a few enthusiasms: the bleak, experimental music of Coil; the avant-garde folk of Richard Dawson; and the diverse work of the prolific Italian singer, composer and musician Franco Battiato. But his real objective is to provoke reflection on the determinants of our musical taste and, even more radically, to consider whether we are genuinely interested in music at all.

If there is a consistent target, it is snobbery. Reflecting on cruel and condescending salvos against Liberace and Chris de Burgh, Faber asks why certain artists and audiences are selected for derision and why we deem it acceptable to exhibit social prejudice towards those with “poor taste.” These issues suggest more fundamental questions about the trust we place in critics, and the rarely examined assumption that criticism adds value to our appreciation of music.

One of the book’s most powerful segments, concerning the notion of authenticity, relates the tragic story of the duo known as Milli Vanilli. Faber handles this with compassion but leavens the mix with some wry observations about changing attitudes to ideas of reality and simulation.