This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THIS year the Quais du Polar in Lyon, the largest European festival of crime novels and one of the largest in the world, in celebrating its 20th season, was marked by the intrusion into the presentation of new novels by the real-world problems and catastrophes going on around the festival.

Each evening, just outside the festival walls, in front of the town hall, there was a vigil calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, while inside there were novelists incorporating climate apocalypse, rabid income inequality, and the indignity of European cities, most notably Venice and Barcelona, overcome by tourism.

In a panel on encouragement of reading sponsored by Unesco’s “Creative Cities” initiative, the Icelandic crime writer Yrsa Sigurdardottir, who ought to know since she not only helped create and chair the Reykjavik Crime Fiction Festival but has written 15 novels, explained that Iceland has money to give to support all kinds of arts because it is one of the few countries in the world that “doesn’t have an army.”

She suggested, and not totally facetiously, that instead of destroying each other on the battlefield, Russia’s Putin and Ukraine’s Zelensky instead should duel it out by writing alternate chapters of a novel.

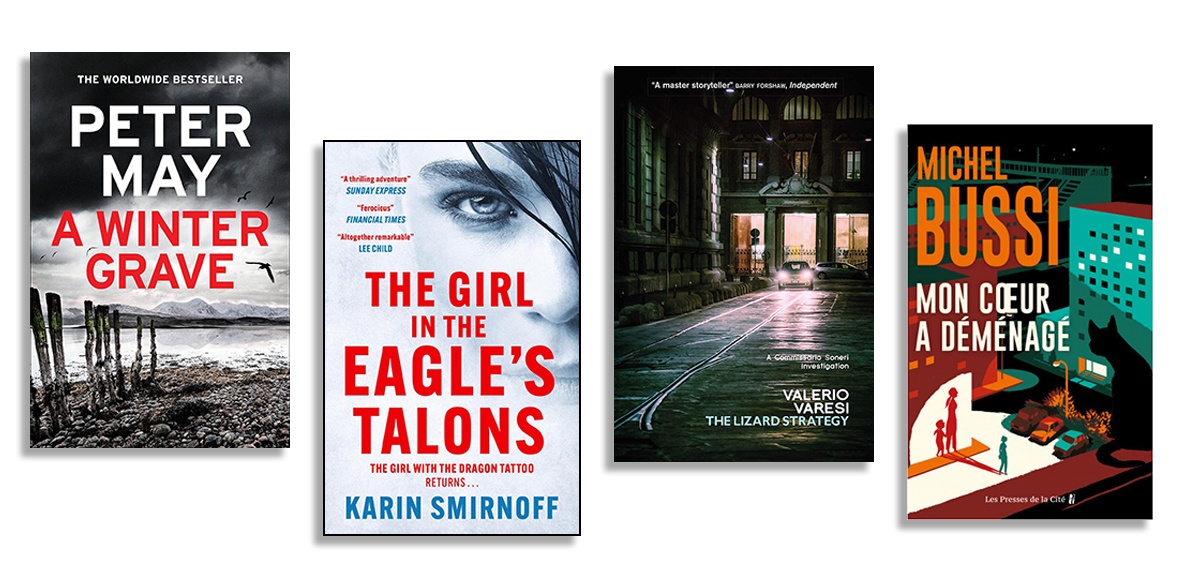

A panel innocuously celebrating co-operation between France and Britain took on a cotemporary air when Peter May recounted why he had come out of retirement to write A Winter Grave (Riverrun, £22), a crime novel set in 2051. In this nightmarish future, the Scottish Highlands are frozen but thawing enough so a dead body is discovered in an icy cave while Glasgow is flooded, filled with acrid odors from the backed-up sewers with cars replaced by Venetian-style water taxis.

May related that after Cop26, the 2021 Glasgow Climate Conference which he attended, he became convinced that the destruction of the earth was not going to be addressed. He was so shocked by this cavalier attitude that he wrote a book in which the context that surrounds the mystery is a failing earth where two billion people are forced to flee their homes.

In a sign that the climate crisis is intruding everywhere he was not the only writer to address this issue, and one panel focused on dystopic worlds to come, a subject that had previously not been central to the crime novel which has always been an excellent way of highlighting contemporary and past corruption but has generally steered clear of the science fiction predilection with the future.

Back in the present again, the devastating effects of fossil fuel and mineral extraction showed up as Karin Smirnoff, who is now charged with continuing Stieg Larsson’s Millennium series with The Girl in the Eagle’s Talons (MacLehose Press, £9.99), and who explained that her sequel is set in the north of Sweden, home of Europe’s last indigenous population, the Sami, where mining interests unearthing material for clean energy batteries often claim they can drill and dig on the land because “nobody lives there.”

Smirnoff, the first female to write a volume of a series which is now subtitled “A Lisbeth Salander Novel” pointing to the popularity of the female character, explained by way of her book that a good deal of harm is done to indigenous lands in the name of safe and clean energy where to get access to the minerals powering batteries the companies “kill six lakes surrounding the mine.” In The Girl in the Eagle’s Talon Salander grows up and becomes a mature activist.

A panel on white collar crime suddenly took an unexpected turn when the Italian mystery writer Valerio Varesi, whose novels are set in Parma in northern Italy’s Po Valley, explained that his subject is the change in his town in the wake of the Reagan-Thatcher 1980s. It was at that point that he observed the market economy driving human behaviour and the thirst for money and profits beginning to dominate human relationships.

Varesi, who is also a journalist for La Republica, explained that after the economic crash of 1929, banks and the financial sector were governed by rules that have since been evacuated, allowing the second crash of 2008. His latest, The Lizard Strategy (MacLehose Press, £9.99), recounts the eerie disappearance of Parma’s mayor just as he is about the be the subject of a corruption investigation. In light of the penetration of capital into all forms of life, he asked the panel a pointed question: “Who governs Europe, Christine Lagarde (president of the European Central Bank) or Ursula von der Leyen (president of the European Parliament)?”

The rest of the panel refused to take up the question and the moderator ordered Valerio not to pursue the subject further.

A regular guest at the festival is France’s most popular crime writer Michel Bussi whose novels are often diverting page turners but who this year appeared at the conference with his latest, My Heart Has Moved (Presses de la cite, £13.65), which confronts the problem of increasing inequality in his town of Rouen.

Bussi is a political geographer turned novelist and he explained that the town is now more strictly segregated into the rich more conservative right bank and the poor more radical left bank with the schools on the former now much less open to students from the latter. His novel is about the lifelong quest of a boy whose mother is murdered seemingly by his working-class father but who then discovers that the apparent truth may not be the case.

This year’s Quais du Polar showed that the crime film, long a staple of exposing graft and corruption, is growing up as well and taking on the steadily accumulating and disturbing problems of an ever more complex world.