This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

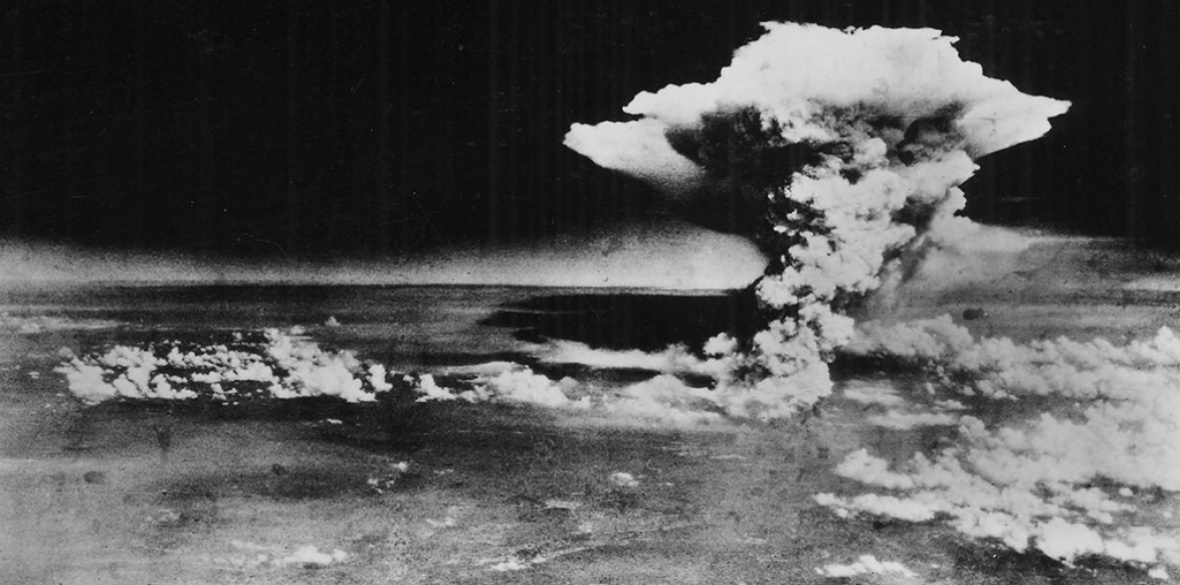

AS we remember the terrible events that took place in Hiroshima and Nagasaki 73 years ago, we cannot avoid the awful realisation that we are closer to nuclear war than at any time since the height of the cold war.

Earlier this year, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved the hands of the Doomsday Clock to two minutes to midnight, the closest they’ve been since the 1950s. To understand much of the reason we need look no further than the US White House.

Already this year we’ve heard the media talk of the possibility of World War III. As we pull back from the nuclear brink one week, we veer closer to it the next.

This seems to be the new normal under President Donald Trump, currently on a roller coaster of wildly conflicting messages — simultaneously bringer of peace to East Asia and harbinger of war in the Middle East.

Of course, this is what we’ve come to expect from Trump, but whatever occasional perks his unpredictability may seem to throw up, the reality is that the trajectory of his foreign and military policy is bad and dangerous.

Trump’s presidency has ushered in a new era of militarism and recent policy documents indicate preparation for high-tech massively violent wars against Russia and China.

Trump’s new defence strategy states that the US will compete for dominance against its long-term strategic competitors — Russia and China — now designated as “revisionist powers” that wish to reshape the world consistent with their “authoritarian model.”

“Rogue regimes” are still a focus for concern, but the “war on terror” is downgraded — no longer the central military priority.

The new approach shifts the big picture focus away from the Middle East and extends Barack Obama’s focus on China to encompass the entire Eurasian landmass.

With the emphasis now away from asymmetrical warfare with non-state actors to war with major powers, the risk of nuclear confrontation and war is increased.

The recently published new US nuclear posture review develops this framework and makes nuclear war more likely.

It takes the lid off the restraints on both new-build and nuclear weapons use.

The most significant element of the review is commitment to a whole new generation of nuclear weapons, with the emphasis on low-yield, often described as “usable,” nuclear weapons. It should be pointed out here that the bombs used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki are technically low-yield in today’s parlance, so we are not talking about something small.

This goes hand in hand with the recently announced $1.2 trillion programme for nuclear weapons “modernisation.” Of course, the US is not the only one to “modernise” its nukes.

Russia is also undertaking such a programme, although it is worth noting that its goal is to phase out and replace all Soviet-era strategic nuclear weapons systems.

This process, which has been under way since the late 1990s, is around 70 per cent complete, due to be finished in the mid-2020s.

Compare that to Britain, which is currently in the Trident replacement modernisation process, where we are now onto our second post-cold war system — Trident and now Dreadnought.

China too is modernising and expanding, albeit from a very small start — its arsenal hovers, size-wise, between those of France and Britain.

Perceived threats to China, resulting from the US military build-up and “pivot” towards Asia, following on from decades of Nato expansion and now exacerbated by Trump’s new defence strategy, mean that China may seek to be a greater nuclear force, linked with Russia to counter the US drive to dominate Eurasia.

When they moved the Doomsday Clock to two minutes to midnight, the atomic scientists cited nuclear risk, climate change and emerging technologies as the key drivers for catastrophe. But of those three, they put nuclear centre stage, highlighting “reckless language,” spending on new nukes and provocative military exercises.

It’s easy to point the finger at the US in this regard, with Russia following close behind. But again, if you look at Britain’s record, we’re up there with the worst of them. How eager are some of our ministers, and indeed Prime Minister, to assert that they would press the nuclear button? Surely this too is “reckless language.”

In terms of spending on new nukes, the lifetime cost of Trident replacement is £205 billion and rising. And when it comes to provocative military exercises, Britain has significant involvement in Nato exercises that take place on an enormous scale — around 100 in 2017 alone.

Major exercises have taken place in Scotland and recent B52 exercises over the North Sea were run from UK bases.

If the first year of Trumpism is anything to go by, there is a dynamic in world politics that seems to be inexorably leading towards greater global tension, conflict and war.

This is bad enough, but, if you add the possibility of nuclear war, it becomes a vision too terrible to contemplate. At this time, when our thoughts turn to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there can be no more fitting tribute to the hibakusha survivors of those bombings than to recommit ourselves to working for a world of peace and justice, for a world without nuclear weapons.

Here in Britain, that means scrapping Trident and cancelling its replacement. No ifs, no buts.

Kate Hudson is general secretary of CND.