This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

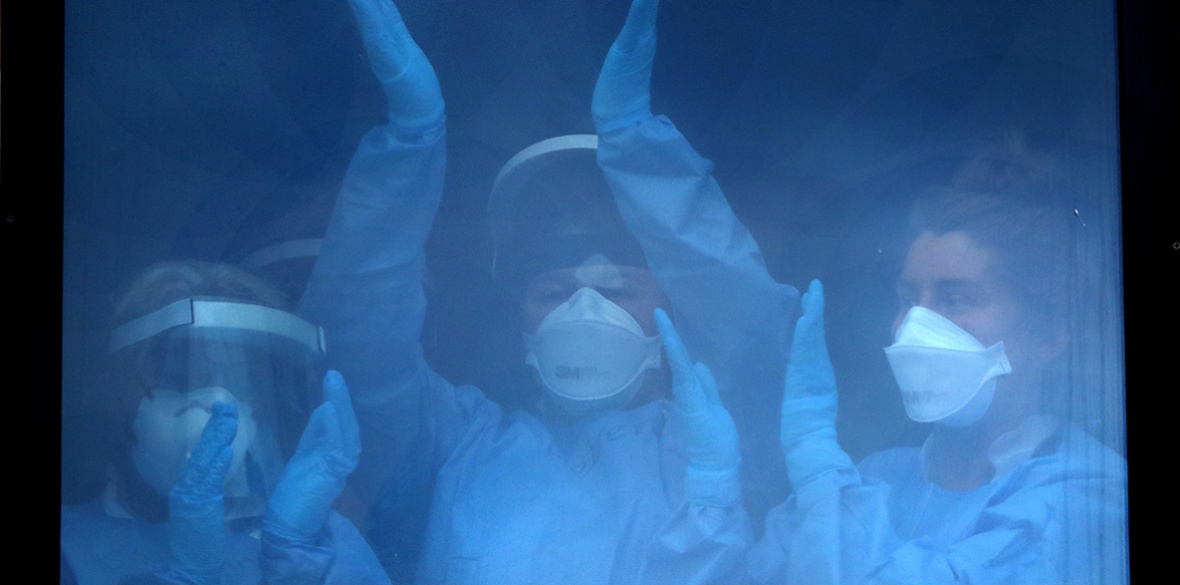

TODAY’S reports from the People’s Covid Inquiry make harrowing reading.

A consultant in emergency medicine describes hospital staff having to research their own procedures during the first wave and, by the second, being exhausted and demoralised.

A train driver details the consequences of the government’s panic closure of 40 London Underground stations and a bus driver the lack of any PPE until five months into the outbreak, while a university professor in occupational health documents PPE supplies lying undelivered at the docks.

Each story explains why, for much of the past year, our country, supposedly with a developed economy and a publicly run health service, has suffered one of the highest death rates in the world: 127,000 people so far.

They expose the real reasons: a health service corroded by outsourcing to private contractors, local government care privatised and a government that has bent continually to the demands of business to maximise workforces, keep schools open and, in doing so, sacrificed the lives of thousands of key workers.

Nor should the relative success of Britain’s vaccination programme breed any complacency.

Globally, the world’s population still stands at risk, the vast majority without any immunity from vaccination and so far no realistic plans to provide it.

Until this is resolved, the emergence of new and possibly more deadly variants is inevitable.

Today, India recorded 314,000 new cases, with its hospitals running out of oxygen.

At the same time, India also produces, and exports, the biggest share of the world’s vaccines — while its own vaccination rate is only 8 per cent.

Here, again, we see the consequences of a global economy dominated by big business and by governments that bend to its will.

India can provide cheap and skilled labour and therefore complete the final stages of vaccine manufacture at minimum cost.

But vaccines have over 3,000 manufactured components, most imported and many from the United States.

On January 21, immediately after his inauguration, President Joe Biden invoked the Defence Protection Act to halt exports of these components.

The ban still stands. India’s commercial producers have been struggling to complete export orders to Europe and other richer countries.

Meanwhile, the Indian population waits — as do the peoples of the world’s most populous countries, in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

The rich can get vaccination. The poor can’t.

According to the British Medical Journal, India’s vaccination programme will take two years to complete.

These figures highlight some other statistics that get little coverage in our mass media.

The worst death rates are currently in EU countries that have suffered austerity and privatisation: the Czech Republic with 2,600, Belgium 2,000 and Italy 1,900 per million.

Yet Vietnam’s death rate is 0.38 per million, China’s 3.4 and Cuba, in face of an international blockade, only 48.

If the figures were reversed, the hawks in the White House would be talking about genocide and demanding regime change.

But the reasons are there to see. All three countries, despite their relative lack of economic development, have more hospital beds and doctors per head than Britain.

Probably still more important, they have cohesive planning of social services, test-and-trace systems that work, significant local popular responsibility and administrations that are not dominated by the needs of big business. When cases occur, targeted lockdowns are immediate.

The hearings of the People’s Inquiry will continue. It will be important, particularly during elections, that they get the maximum publicity and lessons are drawn about the continuing assault on the NHS and public services and the role of trade unions in preventing even worse.

But we should not ignore the wider lessons about the impact of big-business globalisation — or the need for socialism.