This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“THE Labour Party was formed out of the trade union movement to give working people their own political voice. The link from the workplace to the party through the affiliated trade unions is what makes it unique to this day. This link is more important than ever as we work together to tackle the urgent problems we face as a country, from stagnating wages to failing public services.”

That is not me speaking, but the Labour Party’s own website in 2021. Only, the party now seems to have little respect for some of its own statements.

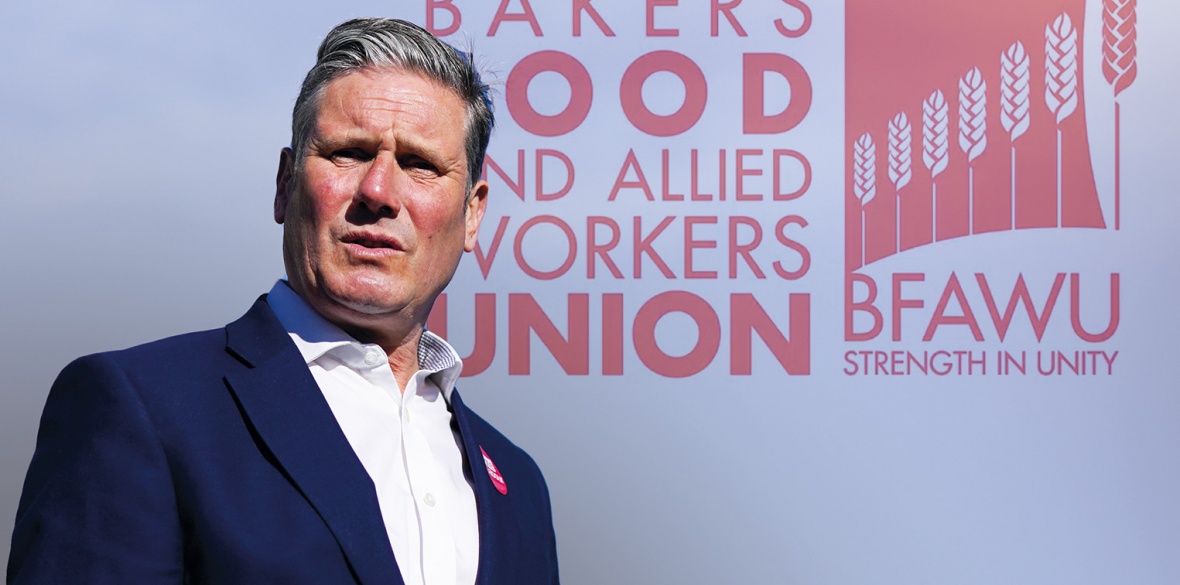

One of the latest targets of its purge of left-wingers is the national president of one of the oldest unions, who has traditionally organised among very poorly paid workers. He is Ian Hodson of the Bakers, Food and Allied Workers’ Union (BFAWU), currently in receipt of a letter threatening him with potential expulsion dressed up in the Orwellian euphemism “auto-exclusion.”

Hodson’s union can trace its lineage back to the Manchester Friendly Association of Operative Bakers established in 1849. By 1854 it was led by another Hodson — Thomas Hodson. No relation, Ian tells me, but he’s pleased by the coincidence and has a picture of his namesake on the wall of his union office.

In 1861, the first Hodson led the formation of the Amalgamated Union of Operative Bakers (AUOB), bringing together unions in Bristol, Cheltenham, Hanley, Liverpool, London, Newcastle, Warrington and Wigan, along with his Manchester society.

The union relocated its headquarters to London back in the 19th century, but the majority of its members then were still from Lancashire. The current Hodson — Ian — worked formerly as a biscuit baker at Symbols Biscuits in Blackpool.

The AUOB was one of the earliest unions to give financial support to the fledgling Labour Party, cementing that crucial industrial and political link in 1902.

The key period that prefigured the Labour Party coming into being as a political expression of the trade union movement is seen as 1888-89 when there were epic struggles by female matchworkers at the Bryant and May factory in Bow, East London in June-July 1888, gasworkers at Beckton in the spring of 1889 and the Great Dock Strike of late summer and early autumn 1889.

East London was the cradle of these struggles for shorter hours and better pay in safer workplaces, though the first burst of militancy in that district in those years, a few weeks before the matchworkers’ strike, barely registers a footnote.

This was a strike led by immigrant Jewish bakery workers who had fled persecution in the Russian empire and were now fighting in their new adopted land against 16-20 hour shifts with few breaks.

They took spontaneous strike action, marching from bakery to bakery with a few musicians playing stirring music, to call workers out. Some 300 bakery workers were eventually involved, winning support too from German immigrant bakers in the East End. Their gains were minimal but the example of workers organising collectively left its imprint.

In the wake of the successful Great Dock Strike a year later, involvng many tens of thousands of East End workers, two of its leaders, Ben Tillett and Tom Mann, wrote about the “new unionism” of the ultra-exploited unskilled and low-skilled workers that had been born through these struggles.

They wrote, “the real difference between the old and the new unions is that they do not recognise, as we do, that it is the work of the trade unions to stamp out poverty from the land...

“We are prepared to work unceasingly for the emancipation of the workers. Our ideal is the Co-operative Commonwealth — for families to procure not merely the necessaries of life as ordinarily understood but everything that conduces to the elevation of humanity.”

One important strand that emerged was syndicalism, which stressed that economic and political change could be brought about by militant industrial struggles by workers, but the more enduring expression was in the idea of forming a political party that would give a powerful collective voice to the needs and demands of working-class communities.

Pledge number seven of Keir Starmer’s “10 pledges” to Labour members on which he was elected as party leader was to “strengthen workers’ rights and trade unions” — working “shoulder to shoulder with trade unions.”

It is hard to see how the targeting of BFAWU’s national president — who works day in, day out for low-paid workers — for expulsion matches that pledge. Mind you there has been precious little sign of any of Starmer’s other pledges being acted on. But this action against Hodson seems also to symbolise the desire among Labour’s leaders and influencers to break the fundamental link between the party and the conscious collective struggles of working-class people through their unions.

While the Labour Party “under new management” continues to show how acceptable it is to businesses and Middle England, BFAWU, meanwhile, continues to spearhead key campaigns for better working conditions in the food industry; for food workers not to be priced out of purchasing the food they produce; for Statutory Sick Pay (SSP) for low-paid workers, especially women and workers on zero-hours contracts who don’t meet the threshold for SSP of earning £120 a week. And BFAWU are seeking to unionise the precariat who work on zero-hours contracts in the super-exploitative fast-food industry.

These are the campaigns against Tory-imposed misery that the Labour Party ought to be putting its full weight behind, but it can’t when its main priority seems to be an internal war on the left of the party and even on trade unionists who are standing up to that misdirection of the party’s energy and resources. Meanwhile the Tories, the party of the millionaires and billionaires, are laughing all the way to the bank.