This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THOSE readers who ramble along with me most Fridays will know how much I love tortoises, turtles and terrapins. They are among my favourite, most interesting forms of wildlife.

Sadly the most famous of them — the 13 species of giant and aged tortoises of the various Galapagos Islands, 600 miles off the coast of Ecuador — are in the news at the moment. They are being caught and eaten, or sold for their delicious but very expensive meat.

These giant reptiles can live for nearly two centuries. Males weigh up to 500 pounds (227kg). Females only reach 250 pounds (113kg).

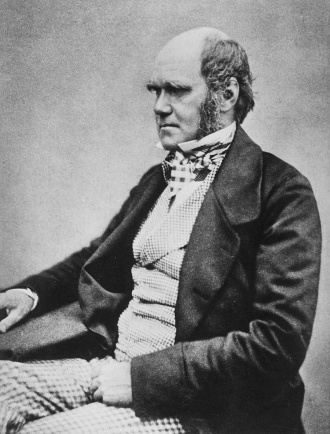

The various species — different on different islands — were very important to Charles Darwin who used observations of these various Galapagos tortoise species when he developed his amazing theory of evolution in the 1830s.

Ironically Darwin himself ate many of the what were then very common reptiles. Darwin noted their flesh had a particularly delicious buttery taste and texture. Many visiting sailors took away the live tortoises as a convenient source of fresh meat.

Today the animals are all protected and all their island homes are incorporated in a giant chain of national parks.

Ecuador, which controls all the offshore Galapagos Islands, has launched an investigation into the killing of the four Galapagos giant tortoises, which prosecutors fear were hunted and eaten or sold for meat.

Remains of the reptiles were found in the national park on Isabela, the largest island of the Galapagos archipelago. Killing the endangered animals has been banned since 1933 but more than a dozen have been hunted and killed in the last two years. Poachers who hunt them now face up to three years in jail.

Last year in September 2021, park rangers found the remains of 15 Sierra Negra giant tortoises on Isabela island. Photos of their huge empty shells — called carapaces — were widely shared on social media and caused outrage all over Ecuador and the islands. Evidence gathered at the time suggested the 15 too had been hunted for their meat.

Ecuador’s attorney general’s office has opened an investigation into the latest deaths of four giant reptiles and experts will carry out post-mortems on all the remains and huge empty shells and a unit specialising in environmental crimes is collecting witness statements from national park wardens and local populations.

As well as poaching for food, giant tortoises have always also been captured for the exotic pet trade.

Just this March, 185 tiny baby tortoises were seized at Baltra airport. They were due to be flown to mainland Ecuador. The baby giants were thought to be less than three months old.

The reptiles had been wrapped in plastic and were found in a suitcase during a routine inspection at the main airport on the island of Baltra. Ten of them had already died, officials said.

One of the biggest threats to Galapagos tortoises is illegal trading for animal collectors and exotic pet markets.

Officials combating wildlife trafficking say even just hatched-sized juveniles can fetch sums of more than £3,600 ($5,000) per animal. They are trafficked mainly via the huge multimillion-dollar exotic, and illegal pet trade centred in Florida but supplying rich and unprincipled collectors all over the world.

Organised crime in the US is now into the exotic wild animal trade. Weight for weight smuggling giant tortoises can be more profitable than smuggling cannabis.

It is believed the smugglers wrapped the tortoises in plastic to immobilise them but the X-ray machine’s operator at the airport nevertheless grew suspicious and finally found them.

The history of the exploitation of these huge but interesting creatures is far too long and complex to relate here in full.

You could say it started with Darwin. When he left the Galapagos on the Beagle the ship’s decks had many live giant tortoises lashed aboard. No, they weren’t Darwin’s specimens for research. They were simply fresh meat stocks for the long journey home.

The tortoise is the largest cold-blooded terrestrial herbivore found on Earth, it plays a critical role in the biostability of the Galapagos.

Numbers of Galapagos tortoises have declined by 85 to 90 per cent since the early 1800s.

Between the 1790s and the 1860s, whaling and fur seal hunting ships, many of them British, systematically collected tortoises in far greater numbers than the buccaneers preceding them. Some were used for food and many more were boiled down for high-grade turtle oil.

A total of over 13,000 tortoises are recorded in the logs of whaling ships between 1831 and 1868, and an estimated 100,000 were taken before 1830.

Walter Rothchild (1868-1937) was one of the family who brought so many species into this country to decorate his and other aristocrats’ woodlands.

Rothchild had a herd — if that’s the word — of giant tortoises on his Tring estate where he would ride on their backs.

In all he had 144 of these gentle beasts. He had sent explorer Charles Harris to the Galapagos Islands to collect the various species of giant tortoises.

Most were kept on the island of Aldabra in the Indian Ocean but others were shipped to Tring in Hertfordshire. His aim was in part to protect them from hunting and potential extinction in their native habitat.

As well as riding tortoises, Rothchild drove a coach pulled by three zebras and a lead horse. He introduced various small deer including muntjac which are now such a pest in our forests and woodlands.

Rothchild presented his largest and oldest giant tortoise to London Zoo. Amazingly it was this tortoise I actually rode on at the zoo as a toddler.

Sometimes, he would get on their backs and ride them. He did his best to figure out the mysteries of their evolution and taxonomy.

The prize of his collection was a great Galapagos tortoise named Rotumah. When Walter acquired him, Rotumah was reputed to be the largest tortoise in the world, and was thought to be at least 150 years old.

Rotumah had lived for many years on the grounds of a lunatic asylum in the suburbs of Sydney. He arrived deeply chilled and near death after his steamer voyage to England.

He made a swift recovery, only to die two years later. Sadly his mate had been left behind in Sydney — sounds to me that Rotumah died of a broken heart.

Today there are currently about 15,000 of the giant tortoises in the world, compared to 200,000 in the 19th century and now some people are eating them.

I’ll finish with the tale of a much smaller, but closely related, animals. Small terrapins, normally the red-eared species, have long been available in British pet shops.

These red-eared terrapins have been living here wild since the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle craze in the 1990s.

Bought as pets they were dumped in ponds and rivers when they grew too big or had given their young owners a painful bite.

Experts believed that terrapin eggs needed a temperature of 30°C for 60 days to hatch but rare sightings of newborn terrapins seem to suggest otherwise.

Global warming is making those conditions more and more likely in Britain particularly if they are helped by canal and riverside businesses pumping warm water into canals creating warm micro habitats.

The red-eared terrapin is a native of the US, Mexico and South America. They grow to about 30cm (1ft) across and often carry the disease salmonella. It is illegal to release them into the wild but many escape or are released every year.

All over our inland waters these terrapins — and other small turtles — are becoming more and more common. There is a healthy colony at the London Wetland Centre at Barnes. I often see them in the ponds at Cambridge University botanical gardens.

The rangers on Hampstead Heath’s ponds in London wage a constant battle with the sliders more at home in the waters of Florida’s Everglades.

More and more these exotic visitors — some now as big as dinner plates — are being spotted on canals, slow-flowing rivers and in ponds and lakes.

Any terrapins, fresh water turtles or tortoises living here are invasive species and as such can undermine established food chains and interfere with natural biodiversity.

But at least they will never get big enough to ride on.