This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

RICHARD HOUSE (RH): Could you tell us something of how your own involvement in, and experience of, our schooling system have informed your views about what’s wrong with the English system, and what needs to change?

SIR TIM BRIGHOUSE (TB): In 1950 aged 10 I was school-phobic — weeping myself to sleep, vomiting every morning and dreading the weekly shift in the seating plan according to my class work.

But my dad lost his job and we moved to Lowestoft, where the school badge was the rising sun and had an atmosphere to match.

Life was suddenly wonderful. Long before research showed just how much, I knew that schools mattered, and could change the behaviour of teachers and pupils alike.

Unsurprisingly, that’s what I wanted to be involved in, first as a teacher and eventually — after two 10-year periods as first Oxfordshire’s and then Birmingham’s chief education officer, sandwiching a period running a university department of education and training teachers, I ran the London Challenge.

So I am keenly aware of the changes for good and ill during that time, which has spanned two distinctly different periods.

First there was an age of “trust and optimism” following the Butler Act of 1944.

Education was a key ingredient of Beveridge — a universally acknowledged “good thing” which we all knew we wanted more of.

Following the oil crisis, some high-profile school failures and Callaghan’s Ruskin speech wondering if leaving things to local education authorities and schools was working, Mrs Thatcher ushered in a second age, which has lasted to this day, of “markets and managerialism.”

RH: What would you say are the characteristics of the two ages, and what can we learn from them?

TB: The first involved a partnership based on trust among central government, local government and the schools: civil servants, education officers and teachers working together under the guidance of democratically elected ministers and councillors.

Most influence was with local education authorities (LEAs) and the schools: the minister had only three powers.

LEAs built and ran schools, colleges of further education, teacher training colleges, a youth service, adult education provision, youth employment services and, towards the end of the period, a growing network of specialist services for children with special educational needs and disabilities.

The markets and managerialism period has been characterised by the mantra words of the market — “choice” (of schools for parents), “diversity” (of provision and type of school) and “autonomy” (for schools over budget decisions).

There has been fierce high-stakes accountability, with tests and exams backed by published league tables and Ofsted inspections, which has led to heads and teachers losing their jobs.

Education ministers now have over 2,000 powers and seem increasingly unaccountable, while local authorities have lost most educational functions, with expert staff not being replaced.

In summary, too little accountability in the first age, and now, too much in the second.

RH: If you had to strike a balance between the two — too little and too much accountability — what would that be? And where has this left us today?

TB: Let’s leave the two behind us. Yes, we can say the first was stronger on trust with a balanced curriculum, and the second on standards of outcome.

We could say we now know so much more about school improvement, especially in urban areas, and that whereas only 3 per cent enjoyed higher education in the post-war years, now over 40 per cent do, and we have ever better teachers. But we are left with a broken system.

We have thousands of academies (some in corrupt multi-academy trusts), answerable in detail to central government strong on promoting regulation but lacking expertise and staff to run its byzantine complex system.

A curriculum that’s narrow and unfit for purpose, emphasising what it calls “powerful” knowledge and a narrow range of skills while largely ignoring attitudes, values and ideas, and leading to a narrow academic Ebacc promoted both by ministers and Ofsted, and which excludes the arts and the practical.

We have a system designed to fail at least a third of pupils. There’s a pandemic of mental health issues among adolescents.

We have a further education network starved of funds and recognition. The gems in our early-years provision — the maintained nursery schools — are quietly being closed for want of funds, and our network of children’s centres has been decimated through cuts.

“Caning” has long gone, but has been replaced by internal and external exclusion. In many areas there is no youth service, and no thought that our future depends on a healthy, accessible lifelong education service.

So of course we should learn from the past, but the future demands more; and I’m glad to see politicians across the board talking of the need to redouble our efforts to realise “social mobility,” “equal opportunity” and “equity” as a trinity of aims for our system.

RH: Next year will be the 150th anniversary of the path-breaking 1870 Forster Act. What are the most important policy changes you’d like to see a radical reforming Labour government make in the anniversary year of 2020?

TB: The year 2020 is also the 75th anniversary of Clement Attlee’s reforming post-war Labour government! Let’s take this coincidence to implement a new educational settlement for an era of “hope and ambition” with 10 reforms, each requiring more detailed elaboration than I can give here.

1) Early-years programmes of play and language starting with health visitors through teacher-run kindergartens, leading to formal schooling at age six.

2) A school curriculum designed to develop values, attitudes and ideas among the young as well as knowledge and skills — in short, affecting their hearts and hands as well as their minds.

3) Tests and exams nationally set, internally marked, externally moderated and regionally validated by a nominated university and employing body.

4) Accountability anchored in Her Majesty’s Inspectorate (HMI), with random national testing to ascertain standards, regional inspections and democratic regional and local scrutiny/inspection of schools.

5) A new balanced school score card accrediting performance across the full range of desirable school outcomes, not just academic ones.

6) School admissions should be in the hands of the local authority not the school with policies based not on selection but priority for the most disadvantaged and every parent having the right to a place in the school closest to where they live.

7) A regional network of well-funded colleges of further education accessible from age 14 to retirement, and linked to nominated regional universities.

8) Lifelong learning opportunities available to all, with priority plans for the socio-economically disadvantaged.

9) 10 per cent of entry to independent schools nominated regionally with priority given for children in care and an equity tax of half the difference between the private school fee and the local per-pupil funding in state schools, and distributed to help the most disadvantaged schools in the region.

10) All schools to be non-selective academies with representative governing bodies and democratically accountable locally — on the model of the old church-aided schools.

All this demands three underpinning reforms of governance and finance. First, reduce the present unbridled ministerial powers by establishing a statutory standing national educational advisory council (comprising representatives of teachers, parents, employers, universities, faiths, unions, HMI and local government) whose advice ministers would be required to publicly seek before making decisions.

Second, reinvigorate local government through 10 democratic regional authorities — comparable in size and responsibility to the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish Parliament — with members nominated by existing unitary councils, and devolve most ministerial powers and the requirement to maintain minister-approved plans for provision, school improvement and special educational needs services to these two levels.

Third, give local government tax-raising powers, including the control of business rates.

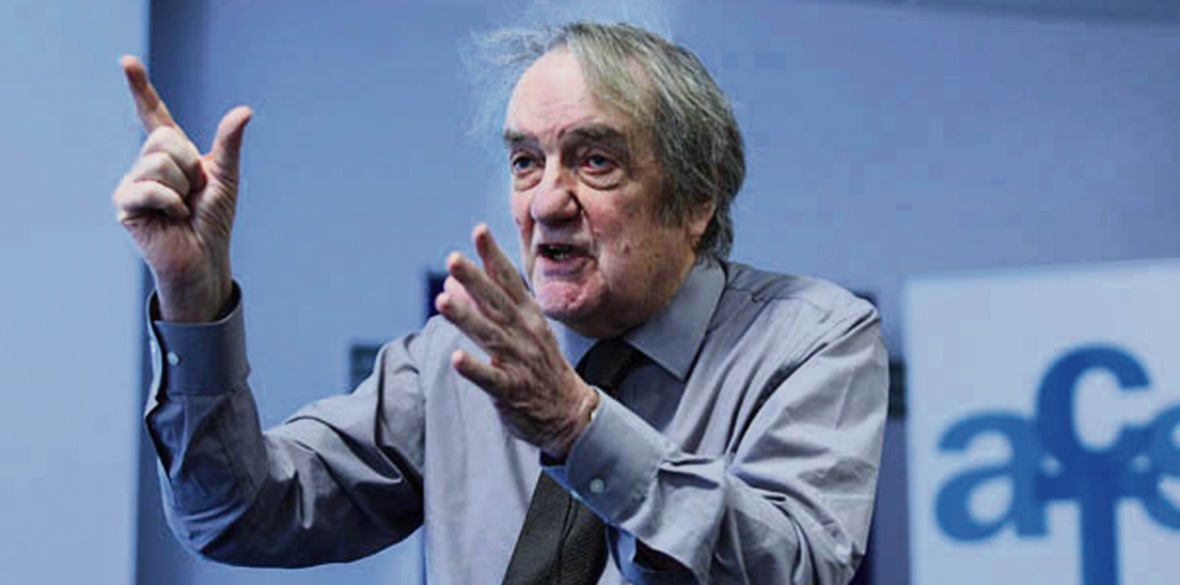

Tim Brighouse is a founder member of the New Visions for Education Group; Richard House is a Corbynista activist and campaigner in Stroud.