This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

“THE twentieth century has been characterised by three developments of great political importance,” Alex Carey noted in his seminal 1995 book Taking the Risk Out of Democracy, “the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.”

The Australian writer’s analysis is well illustrated by the engrossing 10-part BBC Radio 4 series How They Made Us Doubt Everything.

Presented by Peter Pomerantsev, author of the 2019 book This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality, the series looks at how corporate public relations firms engineered doubt about the connection between smoking and cancer in the 1960s and then used similar tactics to manufacture doubt about climate change.

The story begins in December 1953 soon after the publication of an article entitled Cancer by the Carton in the popular US magazine Reader’s Digest. The heads of the major tobacco industry companies hold a secret crisis meeting in New York, having hired John Hill, the founder of Hill & Knowlton, the world’s first international PR firm, to assist them.

“Because of the grave nature of a number of recently highly publicised research reports on the effects of cigarette smoking widespread public interest had developed causing great concern within and without the industry,” noted a Hill & Knowlton memo written a few days later, Preliminary Recommendations for Cigarette Manufacturers. “These developments have confronted the industry with a serious problem of public relations.”

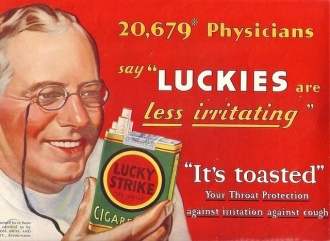

Hill had made his name helping steel companies undermine trade unions and protecting big business. And, true to form, Hill & Knowlton put together the PR playbook the tobacco industry used to protect its profits — most infamously the 1954 A Frank Statement advertisement.

Appearing in nearly 450 newspapers and reaching an estimated 43 million Americans, according to a 2002 article in Tobacco Control journal, the advert emphasised there was no agreement amongst scientists on what caused lung cancer and pledged tobacco industry “aid and assistance to the research effort into all phases of tobacco use and health.”

Ingeniously, Hill didn’t reject the science, but selectively used it to confuse the public. “It is important that the public recognise the existence of weighty scientific views which hold there is no proof that cigarette smoking is a cause of lung cancer,” he argued.

Pomerantsev calls this the “white coats” strategy, with the tobacco industry using scientists often funded by the industry to call into question the work of independent scientists. “You undermine science with more science,” he notes.

A 1969 secret tobacco industry memo perfectly distilled Hill’s approach: “Doubt is our product. Since it is the best means of competing with the body of fact that exists in the minds of the general public. It is also the means of establishing controversy.”

It is now well understood that the tobacco industry’s manipulation of the public delayed regulation and behaviour change, leading to hundreds of thousands of avoidable early deaths. However, years later the playbook was dusted down and put it into action again — this time by an oil industry whose profits were under threat from the public’s increasing concern about global warming.

The stakes were even higher than with tobacco, both in the scale of the threat to humanity and for the companies involved: in 2000 the oil company Exxon Mobil logged $17.7 billion in income, giving it the most profitable year of any corporation in history, according to CNN.

Shockingly, How They Made Us Doubt Everything highlights how Exxon knew about the dangers of climate change and its own role in it by the early 1980s. Speaking to Pomerantsev, Exxon scientist Martin Hoffert explains he successfully modelled the link between burning fossil fuels and climate change in 1981, passing the results onto management. However, ignoring its own research, in 1996 Exxon CEO Lee Raymond stated “the scientific evidence is inconclusive as to whether human activities are having a significant effect on the global climate.”

This was likely part of Exxon’s broader strategy to confuse and manipulate the public about the reality of climate change. A 1989 presentation by Exxon’s Manager of Science and Strategy to the company’s Board of Directors noted the data pointed to “significant climate change and sea level use with generally negative consequences.”

Furthermore, the long hot summer of 1988 “has drawn much attention to the potential problems and we are starting to hear the inevitable call for action,” with the media “likely to increase public awareness and concern.” His recommendation? “More rational responses will require efforts to extend the science and increase emphasis on costs and political realities.”

Discussing the presentation with Pomerantsev, Kert Davies from the Climate Investigations Centre says it shows that “they are worried that the public will take this on and enact radical changes in the way we use energy and affect their business.”

Indeed, by 1988 Exxon’s position was clear, according to a memo written by their Public Affairs Manager, Joseph M Carlson: “Emphasise the uncertainty in scientific conclusions regarding the potential enhanced greenhouse effect.”

Similarly, in 1991 the green-sounding Information Council on the Environment (ICE) — which in fact represented electrical companies in the US — set out its strategy: “reposition global warming as theory (not fact).”

Surveys commissioned by ICE recommended targeting specific segments of the population, including “older, lesser educated males from larger households who are not typically information seekers” and “younger, low income women,” who they believed were more easily influenced by new information. Thankfully, following an embarrassing leak to the New York Times, the organisation quickly folded.

Just as the public’s concern about smoking and health led to industry competitors working together to save their businesses, following the signing of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol committing states to reduce the carbon emissions, Exxon joined forces with Southern Company and Chevron to design a “multi-year, multi-million dollar plan to fund denial and install uncertainty.” This Global Climate Science Communications Plan noted: “Victory will be achieved when average citizens ‘understand’ (recognise) uncertainties in the climate science.”

In many ways this corporate-funded climate denial propaganda campaign was hugely successful in its aims. Pomerantsev quotes the results of a 2016 Pew Research Centre poll of Americans, which found just 48 per cent of respondents understood that the Earth is warming mostly due to human activity, with just 15 per cent of conservative Republicans agreeing.

And like the tobacco industry strategy of doubt, the fossil-fuelled PR campaign has undoubtedly confused the public in the US and beyond and delayed action on the biggest threat facing humanity, meaning perhaps millions of unnecessary deaths. However, there are reasons to believe the fossil fuel corporations are now losing the war.

Speaking to the Morning Star in March 2019, David Wallace-Wells, the author of The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming, explained there have been significant shifts in US public opinion over recent years.

For example, a 2019 Yale University/George Mason University survey found six in 10 Americans were either “alarmed” or “concerned” about climate change, with the proportion of people “alarmed” having doubled since 2013.

A January 2021 poll by the United Nations Development Programme — the largest poll ever conducted on climate change, with 1.2 million people questioned in 50 countries — confirms these hopeful results: two-thirds of respondents said climate change is a “global emergency,” including 65 per cent of respondents in the US.

Indeed, it is important to remember Democrat Joe Biden was elected to the White House after campaigning on what the journal Nature called “the most ambitious climate platform ever put forth by a leading candidate for US president.”

Two important conclusions can be made from listening to How They Made Us Doubt Everything. First, while Pomerantsev himself has written extensively about Russian propaganda and disinformation efforts directed at the West, his BBC Radio 4 series suggests the main threat to the wellbeing of Western publics actually comes from Western corporate propaganda rather than Russian troll farms and cyberwarfare groups like Fancy Bear.

And second, there is an ongoing struggle going on between corporate power and democratic forces across the globe — what former US Democratic presidential hopeful John Edwards called an “epic fight.” The outcome could not be more serious: future generations will only inherit a liveable planet if we are able to successfully confront corporate propaganda and tame corporate power.

How They Made Us Doubt Everything is available to stream or download from BBC Sounds.