This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

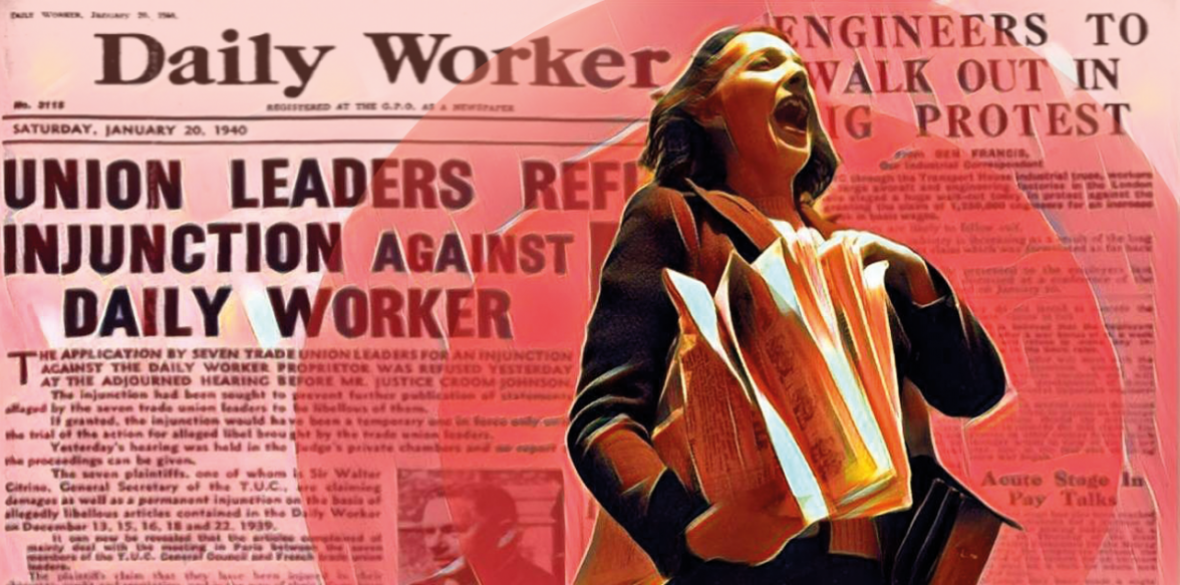

THE Daily Worker, in being and in action since 1930, became the Morning Star 1966. Under whichever name, the paper was and is the only daily in Britain focused on exposing the mechanics of capitalism and challenging its management on behalf of working people.

But in January 1941 the Daily Worker was suppressed by the Winston Churchill government and did not reappear until September 7 1942, 80 years ago today. Popular pressure compelled the government to lift the ban.

Herbert Morrison, then the home secretary for Labour, took the lead in imposing the ban. His memorandum to the Cabinet on December 23 1940 claimed that the paper had “striven to create in the reader a state of mind in which he will be unlikely to be keen to assist the war effort.”

He asserted, states Noreen Branson’s Communist Party history, “Its general line was that the war was being waged by the capitalists for the purpose of benefiting themselves and robbing the workers of such rights and privileges as they had won in the past.”

That the paper’s overall position was much broader than Morrison’s description is obvious from its 1941 New Year’s Day message: “1941 opens with Germany in command of the continent and Britain in command of the seas. The rulers of the imperialist blocs are preparing for years of warfare…

“Last May the government armed itself with emergency powers to control labour and capital. Result: the right to strike disappears and profits increase enormously. We are fighting for a people’s peace, which will dethrone the Churchills and the Roosevelts as well as the Hitlers and Mussolinis.

“And we are not fighting alone. The cry is echoed on the enslaved continent as well as in the far away colonies. Revolutionary leaflets circulate in the darkened towns of Germany, and in France communist activity is increasing. India calls for its freedom.”

Altogether, there was too much anti-profiteering, anti-colonialism and anti-authoritarianism, plus questioning of the government’s war plans and objectives in the paper, for Morrison and the Cabinet to stomach. Police suppressed the paper on January 21 1941.

More background explanation may help to understand the ban. Churchill’s position as prime minister since May 1940 had certainly been defiantly patriotic and expressly dedicated to ending the Nazi regime. But for many socialists in Britain the position was not straightforward.

There was fear of a compromise peace with Berlin, whatever Churchill said. If there was an invasion of Britain, would the appeasers come out of the shadows and take power, producing a version of the pro-Nazi Vichy regime replicating that now in control of much of France?

True, a terminally ill former prime minister appeaser Neville Chamberlain gave way to Churchill as Conservative Party leader in October 1940, and his close associate, “Holy Fox” Lord Halifax was no longer foreign secretary, but many other appeasers were in the Commons and the Lords, and some were still in the Cabinet.

Another concern was that the Churchill government’s primary war motive was to maintain and defend its empire, while continuing to keep democracy out of its colonies and semi-colonies.

India had been conscripted into the war without consultation with its people, and Britain’s military presence in Egypt was potentially under threat from the Italian military presence in its Libyan colony. Should a second world conflict over the possession of colonies be supported?

Like the Tories, the Labour ministers in the Cabinet — future prime minister Clement Attlee, Ernest Bevin, and Morrison — were all for the sustenance of the British empire.

On July 31 1940 Willie Gallacher, the one communist MP, had said in the Commons: “My idea of the successful issue of the war is freedom — freedom for the people of Europe and for the Colonial people… The communists and the Daily Worker… will fight by every means to save the people of this country from the menace of fascism, whether it is from within or without.”

From September 1940, as air raids became routine, the Communist Party began a major campaign for many more bomb shelters, for the opening of “private” shelters to others, and for a transformation of the London Underground Tube into a comfortable refuge from raids.

Police seizures of leaflets and attempts to refuse entry of thousands to the tube failed in their object. The government gave in.

Over these months pay and conditions were held down and profiteering was flourishing. Strikes had been made illegal, while supplies of food were reduced and meat was increasingly unavailable. In all these circumstances the ban was imposed.

Over the next 19 months the war was transformed. First came the Nazi invasions of Greece and Yugoslavia, then the Soviet Union on June 22 1941.

Later came the US’s entry into the war following Japan’s attack of December 7 on the US naval base of Pearl Harbour in Hawaii.

Churchill’s professedly unequivocal support for the Soviet Union was soon put in question. In a Bristol speech on February 8 1942, independent-minded ambassador to Moscow (and Labour Party expellee) Sir Stafford Cripps spoke the truth: “We must get rid of the idea that there are two separate wars in Europe; that we are fighting one of them and the Russians the other.

“We must treat the Soviet Union as our allies in a single war. If we do that; if we work with 100 per cent effort; if we give to Russia all the support we can, then, in my view, there is every chance of Germany being defeated by this time next year.”

But Churchill remained unwilling to launch a second front in France, despite a large public campaign and despite strong and repeated urging, from March 1942 onwards, by president Roosevelt and his military advisers, with the aim of shortening the war.

Support for the paper’s reappearance within the Labour movement became unstoppable before the ban was lifted on August 26 1942. After that “all hands to the pump” got the paper out on September 7.

The first issue, noted George Orwell, was “very mild, but they are urging A) a second front, B) all help to Russia in the way of arms etc and C) a demagogic programme of higher wages all round.”

The paper was also urging the reopening of negotiations with India (which had been refused immediate progress towards independence earlier in the year), and the recognition of India’s right to national freedom.

The paper’s not “very mild” declaration was: “Today is the moment for the second front… At Stalingrad our fate is being decided. It is not somebody else’s city — it is our city.

“If Hitler were to take it, he would take it not from the Soviet Union alone, but from us, from the Americans, the fighting French, the Poles, the Czechs, the Belgians, Norwegians and Dutch and all the Allies whose forces are now waiting on this island.”

On September 9 left-wing MP Aneurin Bevan spoke vehemently in the Commons: “The ordinary working-class people believe that it is the intention of this government to launch a Second Front in Europe.

“If that is not done and if Stalingrad falls and the Russians are driven behind the Urals, the working-class people of this country will be asking why.” He called Churchill’s continuance in office a national disaster.

On September 14 the Daily Worker, unaware of Churchill’s insistence, against strong US preferences for a second front in France, upon a much remoter “second front in north-west Africa,” ascribed the delay in planning a landing on the Continent to “Municheers still in high places.”

But it was Churchill and his military chiefs, and even his Labour ministers, who were refusing a second front in France.

Instead came the mainly US landings in north-west Africa in November (and a consequent shift of substantial German forces to the eastern front), while the Red Army and the Soviet population were left with nine-tenths of the fighting and dying.

But Stalingrad did not fall, and the Daily Worker was in action again. And will stay that way.