This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

SPECIAL BRANCH spied on elected members of the Labour-controlled General London Council (GLC) in the 1980s because of their efforts to improve police accountability, an extraordinary declassified report has revealed.

The 47-page police report from 1983 exposes a Special Branch operation targeting a GLC initiative to informally scrutinise the work of the Metropolitan Police.

The document, which has only come to light recently through the work of the ongoing undercover policing inquiry, contains extensive personal and financial information on dozens of individuals and justice and defence groups in London.

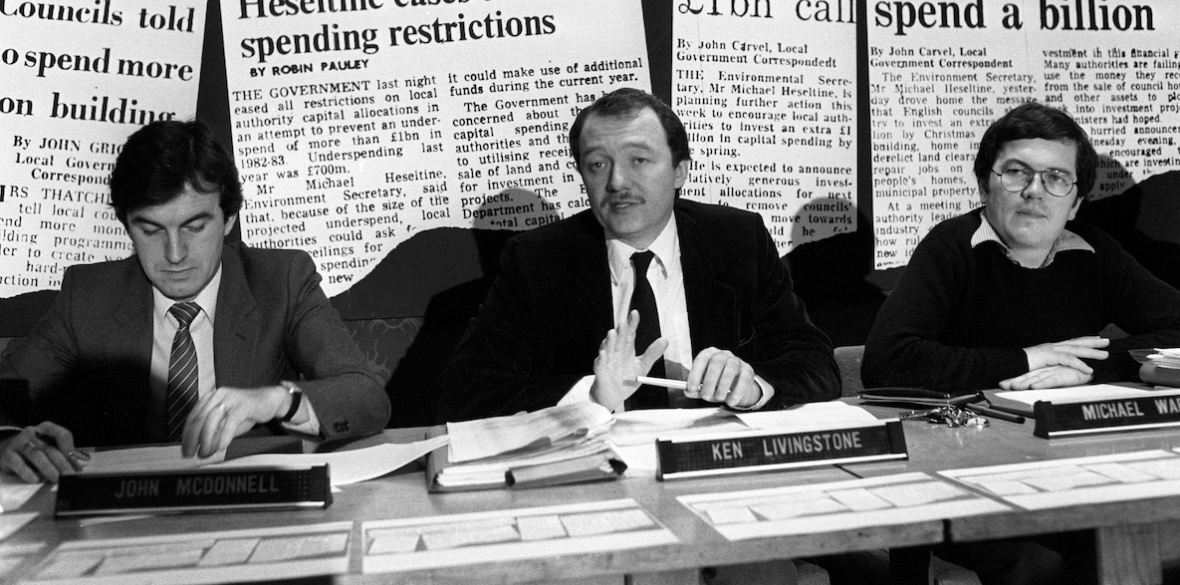

Among those targeted are Ken Livingstone, the then-leader of the GLC and future London mayor, and John McDonnell MP, who are described as “extremists.”

Groups reported on for supposedly being “subversive” include award-winning charity Inquest and the Institute of Race Relations think tank, which are still active today.

Campaigners have described the branch’s targeting of the GLC as an “affront to local democracy,” revealing the lengths the Met was willing to go to “protect itself from criticism and scrutiny.”

Starting a cop watch movement

In the 1970s and 80s, the Met was rocked by a series of corruption scandals and complaints of racist policing and abuse, epitomised by failures to protect minority communities from racist attacks and the police killing of teacher Blair Peach at the Southall anti-fascist demo in 1979.

To address these concerns, the progressive Labour leadership of the GLC, set up a police committee sub-group, established borough police committees in London boroughs, and supported a growing network of grassroots monitoring groups.

The main police committee aimed to serve as an informal police authority for the Met, which at the time was governed by the home secretary, unlike other forces which each had their own police authority. The council believed that the Met should also be accountable to local communities.

“What was in place [before] was not accountable to the people,” explains Tony Bunyan, who worked in the GLC’s internal police committee support unit from 1981 to 1986. “People were being abused, people were going into custody and never coming out.”

The unit steered the police committee and was responsible for approving grants to community groups — one of which, the Monitoring Group, formerly the Southall Monitoring Group, is still active today.

It was also involved in creative ways to ensure police accountability, producing a free monthly magazine called Policing London, and even putting out a reggae track titled Kill the Police Bill in 1984 as part of a campaign opposing a dangerous extension of police powers.

“We all worked together to scrutinise the actions of the police,” Bunyan says. “It stands as a good example of what can be done, if you actually put resources in place.”

This work was part of the GLC’s efforts under the Labour left to champion the rights of minority groups in the capital, which, among other policies, put it at loggerheads with Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who had just begun her 10-year reign.

Thatcher’s battle with the “left-wing extremists in London,” as her officials described the GLC, ended in 1986 after she successfully abolished the council.

While many of the community monitoring groups quickly disappeared without the GLC’s funding, the initiative played an important role in shaping Britain’s long-standing tradition of watching the police, which continues to this day.

A “threat” to the Met

At the same time, Thatcher was waging an open war on the GLC, the secret state was also monitoring the local authority’s democratic activities.

Instead of welcoming efforts to improve accountability, Special Branch viewed the police committee as a threat, describing it as a “carefully orchestrated attempt to secure political control of the Metropolitan Police.”

“From the outset, this branch has attempted to follow the campaign in detail and in so doing has collected a mass of information about the personalities and groups involved,” the 1983 report reads.

That information includes long lists of councillors and campaigners, along with details of their political views, affiliations and even sexual orientation.

The branch collected intelligence on the addresses of the offices of monitoring groups, how much grant money they received from the GLC, the number of people attending meetings and details of what was discussed.

Groups reported on included the Newham Monitoring Project, which continued operating until 2016, and the Gay London Police Monitoring Group which documented incidents of homophobic policing.

Special Branch justifies its operation by claiming that there were “various extremist influences operating within the GLC and its two police bodies.”

Yet these influences are listed merely as membership or links to various left-wing groups or supporting black, gay, or women’s rights, as Sam Jacobs, representing life-long anti-racism campaigner Celia Stubbs, the partner of Blair Peach, noted in his closing submission to the inquiry last week.

Branches are condemned for having members who were “an outspoken Trotskyist,” or having links to “a variety of populist extremist causes, including campaigners against racism.” Livingston’s partner at the time, Kate Allen, is described as a “militant feminist.” In the case of the Greenwich committee, the report admits that it struggled to find an “extremist influence,” but justifies its snooping on the grounds the group would no doubt “become a focal point for militant, anti-police views at least.”

The disdain in which the Special Branch viewed the GLC at the time is apparent throughout the report, as is the defensive attitude of the senior officers who authored it.

It describes the proceedings of the committee as “innocuous meetings with their solemn self-imposed responsibilities and grandiose self-perpetuating designs,” and accuses the GLC of an “irresponsible and almost profligate use of public money.”

Anti-racism campaigners are accused of joining the initiative simply to win “sizeable grants” and the “certain prospect of being able to chide and embarrass the police at every opportunity.”

Scolded by the Home Office

When Special Branch’s report landed on the desk of Home Office civil servant Sir Gerald Hayden Phillips in 1983, it was not well received.

A contemporaneous note reveals Phillips raised concerns to the branch about the “breadth, and tone of and market for” the report, warning it was “dangerous in application.”

In his witness statement to the judge-led public inquiry, the former civil servant, acknowledged that Special Branch had “gone too far,” and snooped on groups “one might consider normal and legitimate political activity which, in my view, was not subversive.”

Extraordinarily, senior Met officers defended the report, saying it was “right that our senior officers should be briefed in order to adequately respond to criticism.”

Despite the serious concerns raised by Phillips, no further action was taken by the Home Office to reign in Special Branch, who said he was satisfied the branch would not stray again.

Were spycops involved?

While much of the information in the report would have been publicly available, references to “secret sources,” suggest some of the intelligence was gathered through undercover officers.

This is of particular importance to the work of the public inquiry, which has been tasked with investigating why black justice campaigns, including several led by bereaved families, were spied on by officers in the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS).

The secret Scotland Yard unit, which infiltrated hundreds of protest groups from 1968 to 2008, and a separate unit that formed later on, are known to have spied on at least 20 family campaigns seeking justice for loved ones killed by police, in police custody or at the hands of racist gangs.

They include the families of murdered teenagers Stephen Lawrence and Rolan Adams, both killed by neonazi gangs in south-east London in the early 90s, as well as the relatives of Ricky Reel, Cherry Groce and Jean Charles de Menezes.

Monitoring groups have played a key role in supporting family campaigns for justice.

Lawyers for the police spies insist that justice campaigns were not directly targeted or infiltrated, and that reporting on such groups was “tangential or collateral to its primary reporting,” on public disorder and subversion.

Why did the police spy on families and accountability campaigners?

The report is significant for police accountability campaigners and families spied on by the state, who say it disputes police’s claims that they were not direct targets.

For Stubbs, who discovered that she was subject to police surveillance for 20 years as she campaigned for justice for Peach, the document is further evidence that campaigns like hers were targeted to serve the self-interest of the police.

In his closing submission to the inquiry last week, Jacobs, on behalf of Stubbs, describes the operation against the GLC as being driven by “Special Branch’s own prejudiced view of the political left, its dislike of campaigns around racism and gay rights and a distaste for accountability.”

He concluded: “Centrally, it is perfectly clear that the Special Branch interest in police accountability groups generally and justice campaigns specifically was one of assisting the force respond to criticism and legal action respectively.”

Campaigners have asked the inquiry to investigate whether this interest informed police decisions to send SDS officers to spy on bereaved families, rather than pouring all resources into catching their loved ones’ killers.

Politicians and monitoring groups react to report

Ironically, the GLC’s model, condemned as subversive by the police 40 years ago, was later adopted nationwide, through the current system of police and crime commissioners, city region mayors and combined authorities.

Today, Metropolitan Police oversight is the responsibility of the London mayor — a policy that can be traced back to the efforts of the GLC to informally scrutinise the force.

As McDonnell, who was the chair of finance on the GLC before going on to become a Labour MP, says: “The GLC was a democratically elected council that simply aimed to ensure there was democratic oversight and accountability of policing in our city.

“This was hardly revolutionary and was a policy that was eventually adopted nationally. The recent revelations of the decades-long ingrained culture of unaccountability in the Met confirms just how right our policy was.”

Responding to the 1983 report, he adds: “There now needs to be full disclosure of the state surveillance of our movement and legislation put in place that prevents this abuse of power by the police and other agencies of the state.”

Bunyan, who went on to become an adviser to the police and director of Statewatch for 30 years, is angry at the “massive” waste of public money and time spent by police to spy on the democratic activities of the GLC while racist killers roamed the streets of London unapprehended.

“It was an attempt to […] try to campaign to hold the police accountable, what was wrong with that?” he asks.

For Deborah Coles, the director of Inquest, the report highlights the importance of groups like hers. “The fact that these campaign groups were being targeted and surveilled by one of the very authorities who perpetuate violence, distrust and secrecy highlights the acute need for [Inquest’s] existence,” she says.

Veteran cop-watcher Kevin Blowe, who was an activist with the Newham Monitoring Group for over 20 years and is now a co-ordinator of Netpol, warns that the targeting of police accountability groups continued today.

“We saw this with the attempt to recruit a Black Lives Matter activist in Cardiff as an informant and we know the movement that re-emerged in 2020 was kept under surveillance.

“The reasons now are the same as they were 40 years ago. To protect the police’s tarnished reputation.”

Follow Bethany Rielly on Twitter @bethrielly.