This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

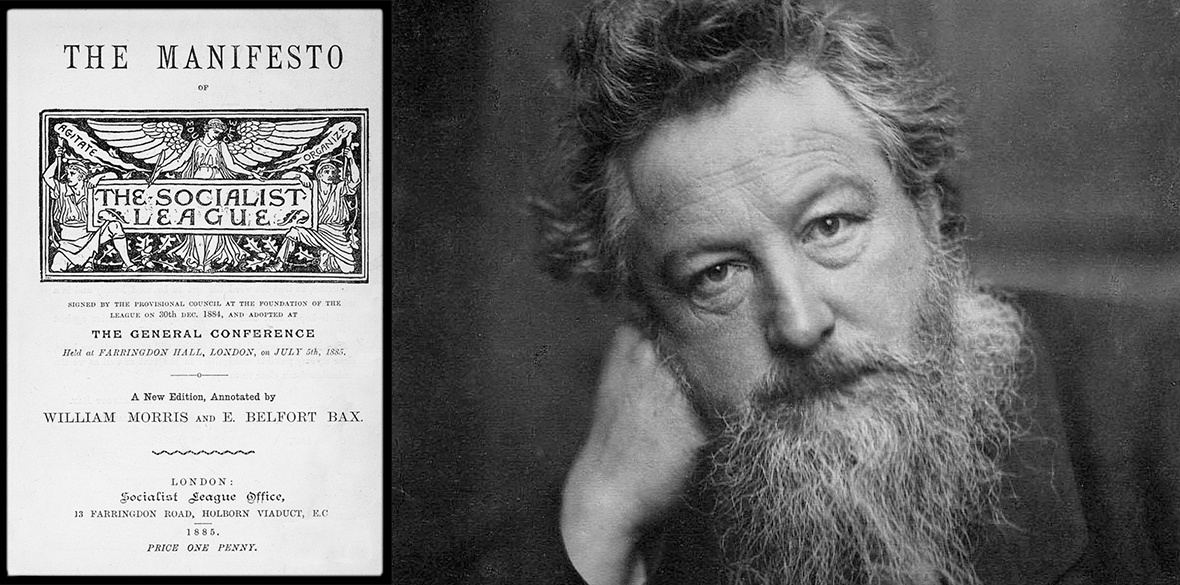

A CENTURY and a half ago, William Morris published an epic which established his reputation as one of the foremost poets of his day.

The Earthly Paradise is essentially a collection of ancient myths and legends drawn from classical mythology or medieval and Icelandic sagas, retold by a group of Norsemen who have fled a plague, setting sail in search of a land of everlasting life “where none grow old.”

They don’t find it but, returning “shrivelled, bent and grey,” they are welcomed into a “nameless city in a distant sea” where they spend the rest of their lives, swapping tales with their hosts.

There’s nothing particularly radical about this “u-topia” (nowhere).

Yet by 1884, Morris had become a committed socialist. On March 16 of that year he was among several thousand people who walked to Highgate cemetery on the first anniversary of Marx’s death.

Of course, marching to Karl’s grave doesn’t make anyone a Marxist and there have always been people who question whether Morris’s socialism is the same as Marx’s socialism.

As poet, craftsman, designer, lecturer and campaigner, a man with immense talent and boundless energy, Morris is such an attractive figure that different factions would like to lay claim to his legacy.

Some reformists have tried to annex him.

MacDonald, Atlee and Blair all claimed to have been inspired by him — which is ironic, because for years Morris denounced reforms (which he called ameliorations).

It was only near the end of his life that he acknowledged that struggles for reforms could be steps on the road to socialism.

He has been called an anarchist — though he broke with the Socialist League when it became dominated by anarchists.

Morris has also been labelled a sentimental socialist with a hang-up about the Middle Ages.

It’s true he believed that the lives of individual craftspeople in feudal times were in some ways better than under capitalism — but is that in conflict with Marxism?

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels wrote: “The bourgeoisie … has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations.

“It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound a man to his ‘natural superiors’ and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment’.”

For Morris, medievalism was at first just an escape from Victorian reality. But it was also, as Marxist historian AL Morton pointed out, a challenge to the ethics and morals dominating society.

Hence the title of EP Thompson’s biography Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary.

George Bernard Shaw wrote: “Morris, when he had to define himself politically, always called himself a Communist … it was the only word he was comfortable with … He was on the side of Marx contra mundum.”

One reason why Morris’s Marxism has often been overlooked is that he wrote in a language very different from that of Marx and most socialist writers.

Marx was grounded in German philosophy; he was concerned to write what could be “scientifically” tested.

So he used the most precise possible terms and often had to explain at great length what he meant by them.

Morris, on the other hand, had very little academic education. He forged his own style of slightly odd but very readable English.

For instance, in his fantasy A Dream of John Ball, Morris imagines a discussion with the rebel priest during the Peasants’ Revolt.

He surprises Ball by saying that although people will indeed be released from feudal oppression, they will still not be free from exploitation.

He says of the future worker: “He shall sell himself, that is the labour that is in him, to the master that suffers him to work and that master shall give to him from out of the wares he maketh enough to keep him alive and to beget children and nourish them till they be old enough to be sold like himself and the residue shall the rich man keep to himself.”

That is colloquial and somewhat archaic, but it’s an accurate account of the creation of surplus value by the worker and its appropriation by the capitalist.

Morris had struggled to read Marx’s Capital (who hasn’t?) but his well-thumbed and heavily annotated copy was one of the first books he bound when he established his printing business.

Creative work was central to Morris’s vision. In his lecture Art and Socialism, he said: “It is right and necessary that all men should have work to do which shall be worth doing and be of itself pleasant to do; and which should be done under such conditions as would make it neither over-wearisome nor over-anxious.”

And he went on: “The price to be paid for so making the world happy is Revolution; Socialism instead of laissez-faire.”

Morris never used the word alienation, but his writings are full of the notion that capitalism alienates people from the control and the results of their work, something that the young Marx was greatly concerned about.

Morris’s utopian novel News from Nowhere describes a proletarian revolution very like the ones Marx envisaged and Lenin led, powered by the organised workers and guided by a disciplined party.

He understood the two stages of socialism, putting it this way: “Communism is in fact the completion of Socialism; when that ceases to be militant and becomes triumphant, it will be communism.”

What Marx called the dictatorship of the proletariat, Morris called “the rule of the useful classes.”

Morris understood the coercive role of the capitalist state, at home and in the colonies.

He wrote: “Remember that the body of people who have for instance ruined India, starved and gagged Ireland and tortured Egypt, have capacities in them — some ominous signs of which they have lately shown — for openly playing the tyrants’ game nearer home.”

Morris came to Marxism in the way that many militants do — by campaigning on immediate issues and coming up against the constraints of capitalism and the hypocrisy of the establishment.

As secretary of the Eastern Question Association, opposing war in the Balkans, he soon found that liberals and radicals would achieve little, so in 1883 he joined the Social Democratic Federation, then the only ostensibly Marxist organisation in Britain — but he was unable to work with the dogmatic and dictatorial HM Hyndman, its founder and leader.

Morris, together with a number of like-minded socialists, including Marx’s daughter Eleanor (and blessed by Frederick Engels) broke with the SDF and formed the Socialist League.

Morris edited and subsidised its weekly journal Commonweal, in which many of his best writings first appeared.

They include Socialism from the Root Up, which, according to Phil Katz, “is one of the first attempts in the English language to develop a Marxist critique of capitalism and present a vision of what might lie beyond it.”

Morris said that in coming to revolutionary politics he had to cross a river of fire, by which he meant the recognition (hard for a man of his privileged background) that only the working class could lead the way to socialism and that progress would come through class struggle alone.

His commitment was always manifest in practical action — not least in helping to establish the Twentieth Century Press located for a period at 37a Clerkenwell Green, now Marx House, the home of the Marx Memorial Library and Workers’ School.

Marx House holds the Hammersmith Socialist Society’s banner (stitched by Morris’s daughter May and which was draped over Eleanor Marx’s coffin) and Morris is featured standing behind Lenin in a fresco, The Worker of the Future, clearing away the Chaos of Capitalism painted in 1934 (the centenary of Morris’s birth) on the wall of the Library’s reading room — well worth a visit if you’ve not already seen it.

Morris and Marx sang from the same song sheet. And today we can still make use of Morris’s legacy, his life and his lectures, to enrich our understanding of Marxism and its relevance to Britain.

Many of Morris’s works can be accessed online at www.marxists.org/archive/morris. The Covid-19 pandemic means that physical access to the Marx Memorial Library and Workers’ School is by appointment only (Wednesday and Thursday) at the moment, but you can find further information on its rich programme of online courses and lectures at www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk where you can also find copies of previous answers in this Full Marx series — this is number 73.