This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

A BROWN paper envelope as well stuffed as a Premier League manager’s payola dropped on to my doormat last week. Sadly, my bung wasn’t full of dosh, but actually something far more meaningful.

This was my first sight of the new recyclable white memorial poppies being introduced this year by the Peace Pledge Union (PPU).

This year the PPU have a new white poppy design, developed in line with their non-violent principles and commitment to the environment.

The first memorial white poppies were originally made in 1933 by the Co-operative Women’s Guild. Today, true to its roots, the new design is made by a workers’ co-operative in the UK.

The new white poppy design is better for the environment. It is plastic free, biodegradable and recyclable in household recycling along with paper and cardboard. A few of clubbed together to get a pack ready for next week.

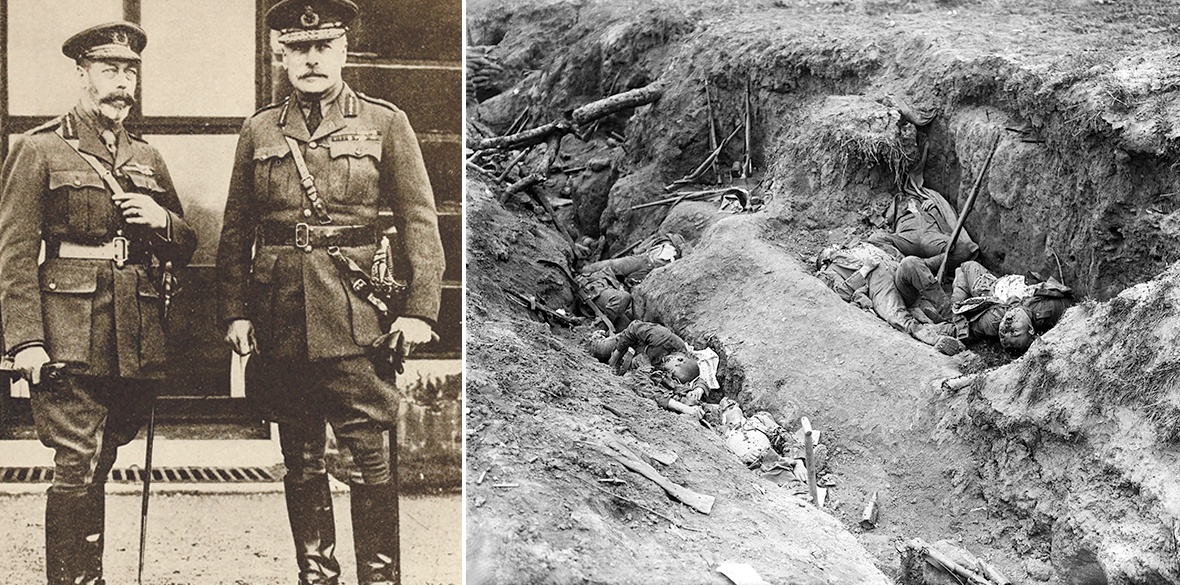

Let’s go back to November 18 1916 when the Battle of the Somme ended. The British press and the officer classes declared it a spectacular victory.

That single battle resulted in a million casualties, nearly 60,000 British troops died on just the first day. In all, the battle lasted nearly four months and at the end the allied forces had moved the front line just seven miles forward.

The battle is part of my wife Ann and our family’s history. Ann’s grandfather Fred, actually perished in the bloody Battle of the Somme just days after he arrived as a young raw recruit in France.

Fred has no known grave. Just his name carved among the thousands on the walls of the Tyne Cot Memorial. He left a widow and four children including young Fred, Ann’s dad then aged just six — the annual red poppy was the only memory of his dad he ever had. No wonder he wore it with pride.

Sixty-plus years on Ann still has fond memories of dad Fred taking her every year to the Cenotaph. Dad would always buy Ann a new winter coat for the outing.

Daughter and dad would inspect the many red poppy wreaths at the Cenotaph and the single colourful wreath of orchids and other tropical blooms celebrating the fact that not all those who laid down their lives were white or British.

Ann and Fred would then walk to Westminster Abbey to the tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Like many others before and since they would speculate if the “unknown” soldier in the Tomb was John Kipling, son of his poet father Rudyard. They and we will never know.

Outside in the garden they would plant their own personal wooden cross and poppy with Granddad Fred’s name on it. Even today Ann still makes sure there is a cross and poppy for both Fred’s planted outside Westminster Abbey every Remembrance Day.

Why is the poppy, Britain’s most colourful weed, seen as the symbol of remembrance? The corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas) — also known as the corn rose, field poppy, Flanders poppy or red poppy — has found itself a unique evolutionary niche.

It probably originated in North Africa or ancient Persia. We do know how it travelled. It hitched a lift in the clay jars of seed corn that ancient traders trafficked all over the then known world.

Ancient farmers in Britain, Flanders and just about everywhere else would buy a bushel or so of seed from a passing Phoenician and get a free bonus of colourful poppy seeds.

They soon discovered that the poppy seed had plenty of uses in bread and cakes and boiled up in a tea it even possessed magical curative powers.

It had developed its tiny rock-hard seed that could last a long time before it found somewhere to grow. Did you know that some poppy seeds found in funereal jars in ancient tombs have been successfully germinated after centuries of dormancy?

That of course is the explanation of the huge flowering of poppies in Flanders. As shells, bombs and trench-digging disturbed the soil, poppy seeds that had lain dormant so long got warmth, moisture and sunlight and burst into ragged scarlet flowers.

Over 10 million soldiers were killed in WWI — estimates of civilian deaths top a million and a half. Poppies outnumbered the dead by far.

As the men returned home, many of them with shell-shock, or what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), they had stories to tell.

Those who had seen horrors in Belgium and northern France also would tell a much encouraging story of the extraordinary beauty, persistence and profusion of the fragile but defiant flower — the blood red corn poppy.

Strangely, it was returning North American soldiers who first adopted the red poppy as an emblem. US organisations arranged for artificial poppies to be made by women in war-torn France. The money raised went to children war orphans.

British soldiers too came back from the grimness of war to find that life wasn’t fit for heroes as they had been promised. Just like today returning heroes found the government off-hand and tardy dealing with their problems.

Some organised themselves into ex-servicemen’s societies of various political opinions and of varying degrees of militancy. In 1921 many of these organisations united to form the British Legion.

Its purpose was to provide support and to fight for the rights of ex-servicemen, especially the disabled, and their families. In fact, what actually happened was it became one of the richest British charities ever.

In 1921 it bought one-and-a-half million of those French-made artificial poppies and sold them to the British public, raising over £10,000 — poppy day had been invented.

Soon it set up its own poppy factory which employed disabled ex-servicemen to make them. Today they produce and sell over 45 million lapel poppies, 120,000 wreaths and one million small wooden remembrance crosses. Just like the one Ann plants to remember her dad and granddad — the two Freds.

Not everyone chooses to wear the red poppy or indeed any poppy. Some see them as glorifying war and militaristic thinking. In many people’s eyes they have become a badge of jingoism and a justification of recent foreign wars. I have no trouble understanding that.

The idea of detaching the poppy from a militaristic culture date back as far as 1926. The No More War Movement suggested that the British Legion should be asked to imprint No More War in the centre of the red poppies instead of Haig Fund.

Douglas “Butcher” Haig was the British general who had ordered so many of his troops to their deaths at the Battle of the Somme. When it came to lions led by donkeys, Haig was certainly our biggest donkey — two million brave lions died under his orders.

Sadly, the Legion chose to keep Haig’s name on their poppies right up until 1994.

In 1933 the first white poppies appeared, mostly home-made and worn mainly by members of the Co-operative Women’s Guild.

Just a year later the Peace Pledge Union was formed and it began widespread distribution of white peace poppies in November each year. Just as today, it took real courage and real commitment to wear the white peace poppy.

As I told you earlier the PPU are still making white poppies. And now, 90 years on recyclable ones.

So, whichever you wear, red or white, both or none, it is your decision. Just remember they shouldn’t be about glorifying war and militaristic thinking but about the respect each of us should feel for those who paid the greatest price in the futility of war.