This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

In simple terms because it engages with the real world and its origins, interactions and change, not (or not merely) with abstractions.

The first chapter of Bertrand Russell’s The Problems of Philosophy (1912, and still used as an introduction to philosophy) titled Appearance and Reality asks whether the table that we sit at corresponds to what we experience with our senses. It concludes: “Doubt suggests that perhaps there is no table at all.”

The book’s final sentence reads: “Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions, since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves.”

That approach — seeing ideas (or the senses) as primary and separate from any “reality” — is known as philosophical idealism.

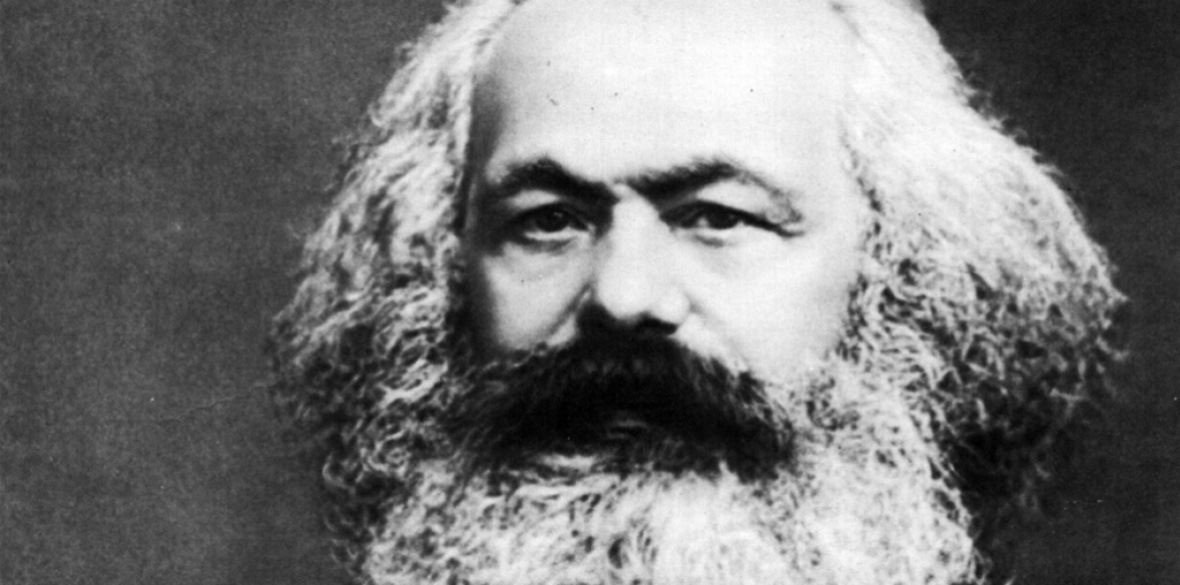

Marx famously declared: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however is to change it.”

Russell, to his credit, and despite his doubts about existence, did try to change the world, opposing the first world war, engaging in direct action for nuclear disarmament and leading opposition to US war crimes in Vietnam. He spent time in prison as a consequence. Like most Marxists, he was “idealistic.” But it’s important not confuse individual idealism (having high ideals) with idealist philosophy.

By contrast, Marxism is a materialist philosophy. The terms materialism and materialistic are often used in a pejorative way to mean concerned or preoccupied with material things, at the expense of values and ideas. But in philosophy the term materialism is used rather differently.

Materialism holds that the world, the universe, “nature,” actually exists and that all phenomena — including consciousness — are ultimately the outcome of, though not reducible to, material processes. It also holds that, at least in principle, humans can work towards an understanding of that world — often incorrectly and never completely, but that over time we can collectively gain a better knowledge of what reality is and how it functions.

This is broadly accepted today, although there are still those who present history solely in terms of “great minds” or the actions of individuals, usually “great men,” independent of their material environment.

At the same time it is important to emphasise that Marxist materialism is quite different from dictionary definitions of philosophical materialism that go something along the lines of “the philosophical belief that nothing exists beyond what is physical.”

Marxists are of course hugely concerned with ideas, values and ethics. They would dispute any suggestion that these don’t exist, or that they can be reduced merely to physical processes. Marxists would insist, however, that knowledge, ideas, values and ethics cannot exist independently of the physical universe. They have a dialectical relationship with that world and, like it, are constantly changing. They need to be understood in their material context.

Marxist dialectics is an approach to understanding the way that everything works, both human and “natural”. At its simplest, it starts from the realisation that nothing is eternally fixed or static. Even things that appear to be motionless are, at another level — as with the atoms in a piece of metal or the individuals in society — in a constant state of flux. The way that things change is not just due to external forces but also to the often opposing (or “contradictory”) consequence of internal processes.

These ideas had already begun to be firmly embedded in science well before Marx: in physics, especially electro-magnetism and thermodynamics; in geology and earth processes; and in evolutionary theory. The significant contribution of Marx and Engels was to recognise them as a general principle which could be seen operating also in human affairs.

For example, dialectical processes can be seen in the interplay of economic, technological and social change which led to the emergence of capitalism from feudalism. Within capitalism the search for profit involves the development of new technologies, which on the one hand displace jobs but may also create new products and markets.

At a more general level, capitalism itself is based on the exploitation by capitalists of a working class whose consciousness enables them to challenge the power of capital and, potentially, transform society into something new.

Throughout their work, both Marx and Engels were concerned to understand not just the internal dynamics of human society but the relations of humans to the universe as a whole. In Capital, Marx emphasised the way that humans are both part of nature and at the same time transform it, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

After Marx’s death, Engels developed dialectical approach to the analysis of pre-capitalist societies with The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. He also extended dialectics from human society to the non-human world in fragmentary essays which were published well after his death as Dialectics of Nature. These included a ground-breaking, and unfinished, essay entitled The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man, building on Darwin’s own observations on human evolution.

Just as materialism is an important antidote to philosophical idealism, so dialectics is counterposed to mechanical materialism.

Mechanical materialism — including the notion that all changes are primarily the consequence of external influences — can be a useful approach in science, especially in physics. Newton’s laws of motion are an example. But especially in biology and in human affairs it can lead to reductionism — the attempt to explain all phenomena solely in terms of processes at a “lower” level of organisation.

Reductionism “explains” society as the sum of the actions of individuals — think Margaret Thatcher’s claim that “there is no such thing as society” — individuals by the functioning of their constituent organs which are in turn understandable only in terms of their cells, then metabolic pathways, chemical processes, and ultimately by the behaviour of molecules, atoms and subatomic particles. This can be a powerful but never more than a partial approach in science, which also needs to understand the behaviour of complex systems, “emergent properties” and the interactions between different levels of analysis.

More sinisterly, reductionism (Marxist philosopher John Lewis call this “nothing buttery”) is also used, as in sociobiology and evolutionary psychology, to justify inequality, women’s subordination and racism on the basis of supposed inherited biological traits.

Dialectical materialism also has its own controversies. For a period it was articulated — both in the Soviet Union and by Marxists elsewhere — as a series of codified “laws” (first put forward by Engels) that became a kind of catechism: the transformation of quantity into quality; the unity and interpenetration of opposites; and the negation of the negation.

Most Marxists today would regard Engels “laws” as an overly mechanical formalisation, at best a retrospective generalisation about how the universe seems to function, that within the Soviet Union under Stalin became formulaic, repetitive — a barrier rather than an aid to creative and critical thinking. Some, however, still claim that these “laws” provide a powerful predictive tool to investigating the world.

Dialectical materialism is best seen as a valuable heuristic — a practical approach to problem-solving, analysis and investigation, not guaranteed to be perfect but a useful rule of thumb, to be continually tested against experience. There’s nothing particularly difficult about dialectics. To quote Engels, people “thought dialectically long before they knew what dialectics was, just as they spoke prose long before the term prose existed.”

But it takes effort. It means not taking any assertion on trust, including those of Marxists themselves. Prominent scientists today assert the value of a dialectical approach in their professional work, for example in mathematics and systems theory, in the relationship between consciousness and the brain, in genetics and human evolution, and in ecology.

And dialectics underpins revolutionary theory and practice. Dialectical materialism is not a magic key to provide the right answer to any question. There have been episodes in the history of socialism where (bizarrely) it was applied mechanically, and it led people — disastrously — up a blind alley.

It is, rather, a fruitful approach to asking the right questions — and to questioning and challenging answers which have already been given — about human society and about nature. It’s arguably central both to interpreting the world and to changing it.

This answer was edited collectively by participants in the Introduction to Marxism series at the Marx Memorial Library and Workers’ School.

Details about the library’s courses can be found at www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk/education