This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

DECISIONS have been made, things are in transit again, and on the outside, it looks like major victories have been won for musicians in Britain.

On April 13, following the pausing of the closure of the BBC Singers, it was announced the BBC is changing its forced cuts to the English BBC Orchestras.

This coincided with an announcement from English National Opera (ENO) which has secured £24 million from the Arts Council England (ACE), with the vision of potentially moving ENO to far flung regions — like Croydon.

There are many positives to take from this, following hundreds of thousands of signatures to petitions, open letters including thousands of leading figures from across the globe, and a rare moment of unity between the Morning Star and the Spectator — BBC and ACE have stepped back on their hack-and-slash vision for music.

But it would be foolish for us to stop at this point.

Overall, these attempts at cuts have been a test trial for both the BBC and ACE.

Cuts can always be threatened, which means arts organisations of all stripes are almost eternally at risk of hacking and slashing — and must be ready to follow the hegemonic worldview they both have to retain that necessary lifeline. Which, given the global political climate could mean the arts as a whole are forced to repeat the “government-approved political line.”

Similarly, these cuts have shown us all a taste of their view of how the arts and society should interact — namely, that the free market rules, good art must be profitable, and why should the plebs have orchestras when they are happy with a chip butty, a pint and the footie?

This is where, to sustain ourselves, we need a long-term vision for the arts in Britain. We need to start campaigning for something much bolder than just “anything but cuts.”

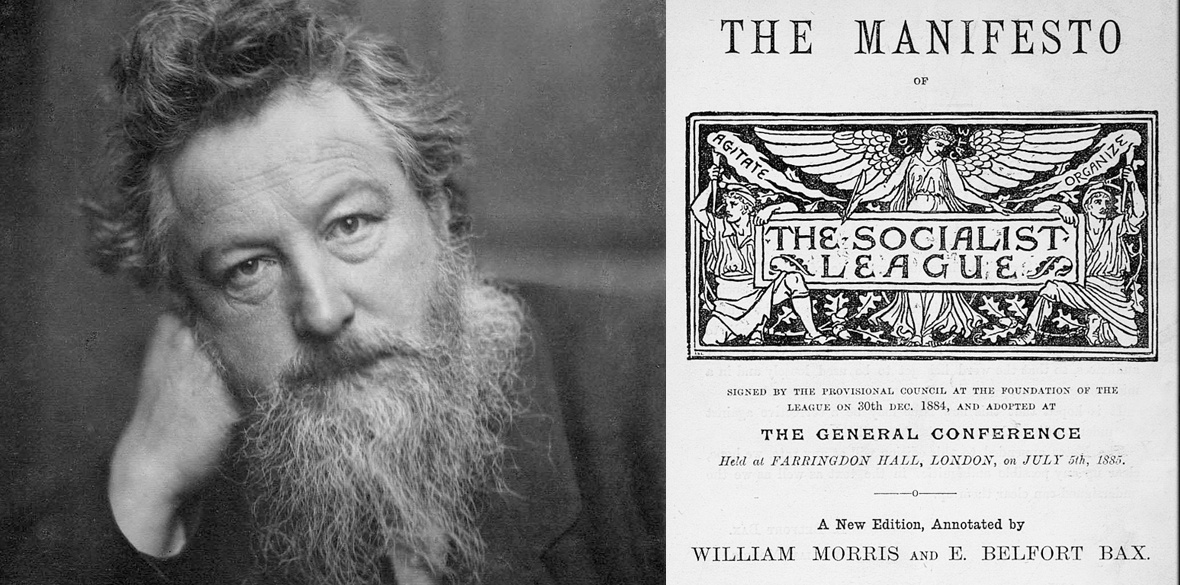

William Morris once wrote: “Here, then, is the truth, which we as artists know full well, that those who produce the wealth of civilised society have no share in art. So entirely are they cut off from it, that many — or most of them, it is to be feared — do not even know of their loss in this matter.”

In his essay from 1884 Art or No Art? Who Shall Settle It? Morris highlighted the particular problem art faced in Britain at that time, namely: a key thing which enriches human life is forcibly robbed from working-class people.

This in turn means art created in society reflects a particular stratum, either through only the wealthy being able to afford such a lifestyle, or those from the working class who manage to break into the arts being forced to cater to tastes which can regularly be against their own interest, or risk poverty and obscurity.

Though we are far from the world in which Morris lived, we can plainly see the positive developments which allowed working-class people into the arts post-1945 are being undone.

With music education being decimated as “too expensive” or schools forced to abandon the arts because they “are not really academic subjects,” the entry points into music and other art forms disappear.

When the number of stable and well-paying jobs disappears, the space for working-class artists disappears through not having the same wealth behind them to “wait” for better gigs.

When arts organisations cut their funding to commission new work, working-class composers, writers or painters cannot make an income, and performance arts like music — to experience work from bygone days — has always have to battle with “relevance.”

How do we beat this, when our tactics currently are only petitions, open letters and general disgust at cuts?

The answer is simple: we need vision and we need idealism.

When the current landscape in the arts strongly works against working-class people, simply stopping cuts only plasters over a particular problem.

This is where the dream of nation filled with culture, bursting at the seams with cultural infrastructure and creators, can drive us to do more. In turn striving for something more, we can find ways to bring more people to our cause — our republic of art.

When we dream of bigger, we can be bold and demand more of those ordained merely to give us crumbs. Force them to do not only do better, but to act with a vision of arts in Britain.

William Morris put it best — “I am bound to assert here and everywhere that art is necessary to man unless he is to sink into something lower than the brutes.”

Art makes us human, and all of humanity deserves art. Let us start looking at how we can give everyone art, lest we sink into something lower than the brutes. Art, or no Art, it’s ours to decide.