This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

CLASS struggle is not, as some would have it, a Marxist conspiracy; it is a fact of social life, a proper subject for historical analysis.

From some 11,000 years ago an agricultural revolution began to end the classless primitive communism of hunter gatherers.

People could now produce more than was needed for mere subsistence.

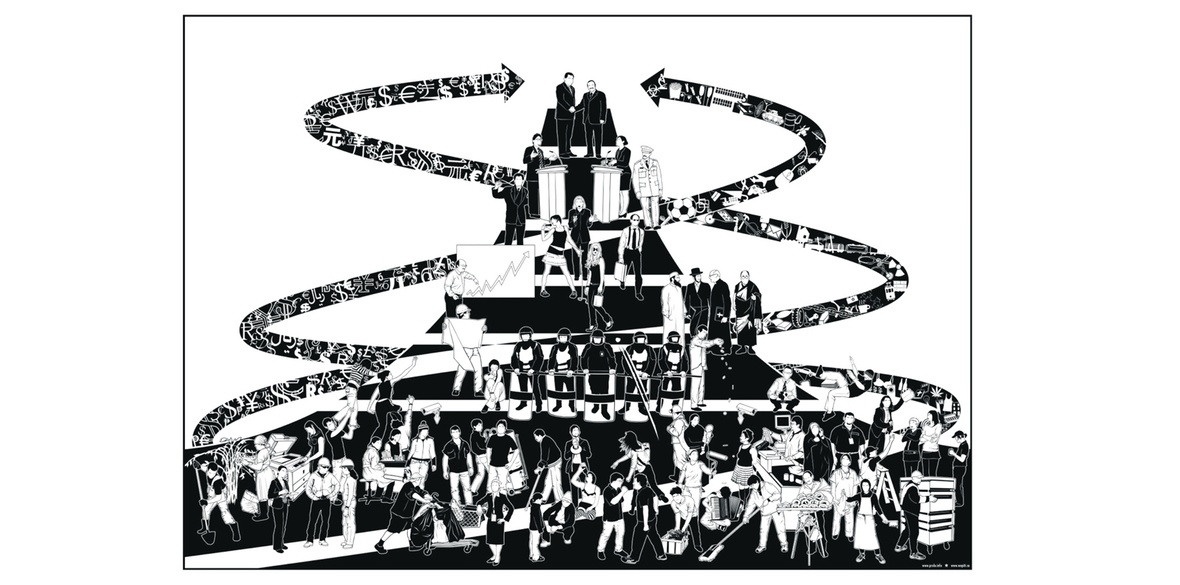

The distribution of that surplus has ever since been fought over by social classes with conflicting interests: exploiting ruling classes, who owned or controlled the land and other means of production, against exploited oppressed workers, who owned nothing of any consequence. That is the origin and basis of the class struggle. The main contenders have been slave owners and slaves, landlords and peasants, capitalists and workers, with various intermediate strata complicating the picture.

The modern class struggle begins in Europe a few centuries ago when groups of merchants, bankers and manufacturers developed within the feudal system. This new capitalist class had to rid society of feudal laws and customs in order to grow. A high point of the battle was the English Civil War in the 17th century. Though fought in religious terms (“high church” versus Puritans) it was in essence a class struggle, resolved when the feudal aristocracy agreed a compromise that enabled capitalist social relations to flourish and dominate.

The same can be said about the American Civil War a century later. Though fought in terms of states’ rights and human rights, it was in essence a class struggle between the slave-owning landlords of the south and the moneyed industrialists of the north.

After the worldwide triumph of capitalism the principal form of class struggle has been between owners and earners. In The Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels recount the stages in the growth of working-class consciousness: “At first the contest is carried on by individual labourers, then by the workpeople of a factory, then by the operatives of one trade, in one locality against the individual capitalist who directly exploits them.”

Then with the growth in numbers comes a recognition of common interest. In Britain this led to the formation of local and then national trade unions, and later to the TUC, the Labour Party and the Communist Party.

Right-wing social democrats, such as most previous leaders of the Labour Party (and influential members of it today) recognise the existence of classes, but believe that the workers benefit more from class collaboration than class struggle. Their favourite example used to be the Swedish compromise. In the 1930s the trade unions agreed to moderate their demands; the employers accepted high taxation; the state guaranteed full employment and good public services.

Something similar happened in the post-war welfare states. In Britain education and health services and public ownership of key energy, water and transport utilities were reluctantly conceded as the cost of social stability and economic growth.

But the consensus broke down, in Sweden as in Britain, when the profits of the big corporations were threatened and the ruling class turned to a neoliberal strategy.

So a period of relative class collaboration led to a period of the most intense class struggle. The work-in at the UCS shipyards in 1972 and the miners’ strike of 1984-5 represent just two of many episodes of resistance to an ongoing attack on the living standards of working people.

These and similar incidents remind us of two important aspects of class struggle. It is usually the employers who are the aggressors, seeking to reduce wages, worsen conditions, or close down whole industries. The working class is forced into defensive action.

And the ruling class has the state on its side. Because it is their state, their army, police force, prisons, law courts, Civil Service, their Tory Party, all run by relatives, friends and beneficiaries of the financiers and industrialists.

The right talks of reducing the role of the state. But the reductions they seek are in the regulation of capital and the provision of welfare; the same politicians seek constantly to strengthen the laws against trade union organisation and action. Indeed, the Marxist view is that the existence of a state, any state, is a response to class struggle.

Particularly in the decades following the second world war, working-class struggles initially secured important growth in what Marx and Engels called “the administration of things and the conduct of processes of production” including a national health service, education, pensions and welfare services, housing, water and energy supply, transport, and environmental and consumer protection — all initially with a large measure of social, municipal or state ownership.

It is precisely these public services — local and national — that have been constantly under attack by the representatives of capital, the political right who have been so busy “shrinking the state” in the interests of power and profit at the same time as they have expanded the coercive aspects of state power — what Marx and Engels called “state power in social relations.”

In this last respect, as Lenin bluntly put it: “The state is a machine for maintaining the rule of one class over another.”

The opening words of The Communist Manifesto are: “The history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggles.”

Can that be true? We have referred to the class struggle embodied in two civil wars and two industrial disputes. And there are many, many more examples of both in the history of every land and every period.

But what about all the other conflicts that fill conventional textbooks? What about colonial wars? The Norman Conquest? The first world war? In all of these one ruling class fought a rival ruling class in order to gain land, resources and more people to exploit and oppress. So yes, they were class struggles. As were the politicking and diplomacy that went on with the same aims.

The class struggle exists, whether we like it or not. It exists because exploitation is an inevitable and necessary feature of capitalism, continually trying to extract more profit, and creating poverty, unhappiness and degradation in its wake. And inevitably, people fight back, to protect their jobs, livelihoods, their families, communities and the environment.

What distinguishes Marxism from social democracy is not recognition of class struggle. It is the view that only through sustained struggle can the working class and its allies win political power, and then set about building the more just and equal society of socialism, and, ultimately, its classless successor — communism.

Marxists maintain that continuing the class struggle has the potential to rid humanity forever of the scourge of class oppression and the burden of resisting it. To do this requires all workers, their families and communities — the many; women and men of every background — to work together in consort to win that struggle and build a new society.

The Marx Memorial Library’s Full Marx column appears every other Monday in the Morning Star. For information about the library, courses and events, visit www.marx-memorial-library.org.