This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art

National Gallery, London

IN 1903, the year of Paul Gauguin’s death, Maurice Denis’s tribute asserted: “He was not the sort of ‘gentleman artist’ that has become so distasteful to us for the past fifteen years — indeed his sensuality was uncommon — but his works were rugged and sound.

“Something of the essential, of the profoundly true, emanated from his savage art, from his rough common sense, and from his vigorous naivety… he invigorated painting again… instead of going serenely to Rome to study antiquities, [he] became inflamed with a passion to discover a tradition beneath the coarse archaism of Breton calvaries and Maori idols, or in the crude colouring of the Images d’Epinal.” (These were popular wood-cut prints).

It was this rage against the polite niceties of academic art in which most pioneers of modernist art were educated, which fuelled their search for a more personal and expressive art.

This revolutionary impetus links the formally diverse works of Gauguin, Paul Cezanne, Vincent Van Gogh, Georges Seurat, Pierre Bonnard, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Kathe Kollwitz, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Jan Toorop, Wassily Kandinsky and others in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Rather than subordinating the means of production to the work’s subject matter, the formal means became central to conveying meaning. Not least through the use of colour.

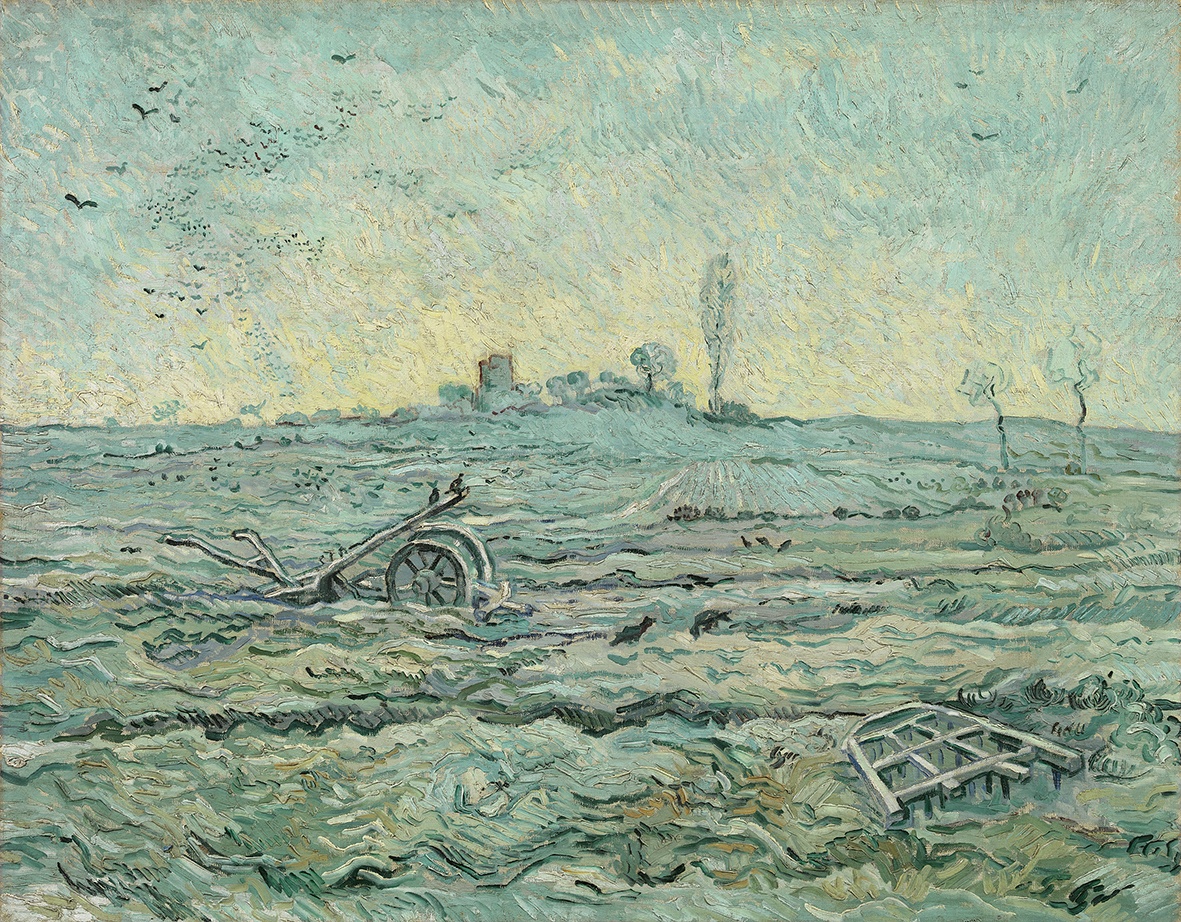

In Van Gogh’s Landscape with Ploughman of 1889, sweeping, visible strokes from his paint-loaded brush with vivid lilacs, yellows, browns, creams and greens convey the labour with which horse and ploughman have energised the placid earth into ripples evocative of heaving sea waves.

The paint strokes are so thick that some may well have been squeezed straight from the tube to the canvas.

In his Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel) of 1888, Gauguin expressed the devout Breton peasants’ supernatural states of mind by using brilliant, non-naturalistic primary colours.

The green grass is depicted in bright red, against which the angel, in a vivid blue robe with yellow wings, struggles with Jacob. The use of bold, flat shapes add to the unnatural, extraordinariness of the event.

In contrast, Seurat and Paul Signac used minute dots or dashes of co-existing complementary colours to convey the vibrancy of daylight in their serene landscapes and seascapes.

Gone were linear perspective and the academic “soups” of tonal gradation — colour alone conveys spatial recession and the quietist, reflective mood of their subjects.

Meanwhile Cezanne’s patient analysis of form and space into small, interlocking facets of colour opened the way for Picasso and Georges Braque’s Cubism in the early 20th century.

By integrating small segments of the subject’s forms with those of the surrounding space they conveyed the complex, ever-shifting viewpoints of human vision, and so furthered the rejection of the fixed certainty of Renaissance perspective which had previously continued to be the bedrock of Western art.

In France, the Netherlands and Germany, Andre Derain, Toorop, Sonia Delaunay, Kandinsky and Schmidt-Rottluff among others pushed further the use of unmixed, and often the raw primary colours of red, yellow and blue to convey states of mind.

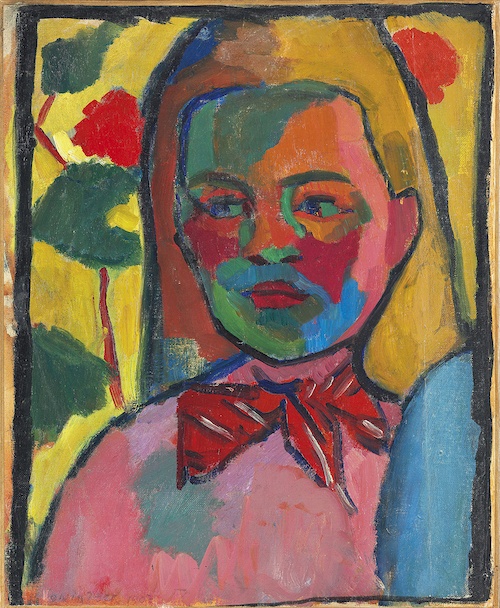

The face of Delaunay’s Young Finnish Woman is portrayed with daring blocks of green, red, blue, orange and pink, while surrounding her with green leaves and red flowers against a yellow background.

The sitter’s expression is serious with a suggestion of doubtfulness, but it is the clashing colours which most express a sense of unease.

Kandinsky’s similarly uninhibited delight in departing from naturalistic colour produced Bavarian landscapes which would delight a child.

And these soon led to his pure, pioneering abstractions in which lines, shapes and blocks of colour whizz and whirl in wild abandon, recalling the atonalism of Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern’s music.

The exhibition was originally destined to be shared with Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Art which has a world-leading collection of Modern art, but the current political tensions put an end to this.

This explains why such an ambitious exhibition drawn from private collections and major European and North American museums is being shown only in London.

The curators nevertheless have managed to secure funding and sponsorship to present a stunning survey of early Modern art.

Organised around the major cities of Paris, Brussels, Barcelona, Berlin and Vienna in which the art was produced and promoted, provides a rare opportunity to see so many influential works in a single venue.

The works’ raw directness and lack of tonal gradation (which shocked the public in their day) still have an immediacy and freshness which make it difficult to believe that they date from a century ago.

And seeing them in the context of the National Gallery’s permanent collection of traditional art enhances their wilful break with the past.

However, the text panels and accompanying book follow a curiously traditional art historical approach, rich in formal analysis which at times veers towards the didactic, but which glosses over the wider social and political contexts which provoked such revolutionary art.

There is little critique or discussion of the concept of the avant-garde, fuelled by an idealisation of artists mostly producing non-commissioned works, which rests on an abstract acceptance of “artistic freedom” which in fact often rested on the economic support of a partner, relative or private income, although it does provide information about contemporary and subsequent exhibitions which included the artists.

This massive exhibition would ideally need to be seen more than once, but even a single visit will be greatly rewarding.

Runs until August 13 2023.