This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

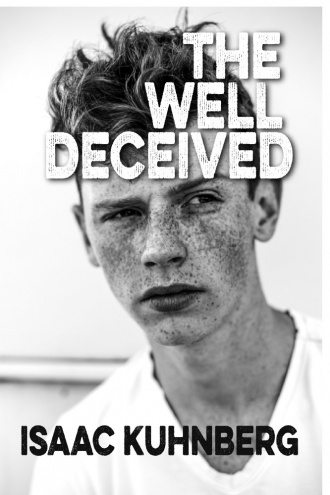

The Well Deceived

by Isaac Kuhnberg

(Clink Street Publishing, £9.99)

READING this novel is a little like singlehandedly putting a cover over a double duvet — a real struggle.

The pseudonymous author attempts to create a world marginally out of register with that of Britain in the 1950s and the reader is trapped for a time in a parlour game of working out what geographically is what, with Alba being Scotland-ish and Anglia England-ish.

Cold and largely unloving places, they're smothered by an authoritarian class structure and unwittingly suffering from a total absence of women and girls.

Main protagonist William Riddle is the smart son of a cantankerous but well-regarded scientist who has made it into Bune, the principal private school in the land.

Any sympathy the reader might have for Riddle’s utter discombobulation at the bullying and ritualisation is undermined by the length of time Kuhnberg spends on elaborating institutional minutiae.

Working your way through dozens of pages that read as a cross between Tom of Finland, Billy Bunter and Harry Potter is struggle enough, but the author’s insistence on constantly mixing humour with grotesquerie is both confusing and inept.

The absence of any narrative urgency ends when Riddle is expelled from Bune because his father has been arrested on unspecificed charges. This is the best part of the book as Riddle encounters the underbelly of an unequal and chaotic society where he has no rights except to be exploited.

Arrested, he's sentenced to a grim youth penitentiary which he escapes, ostensibly to find his father, and during these passages there's a detailed analysis of the country’s democratic processes and heritage.

This includes the platforms and prospects of the main political players — the ruling Pragmatic Party (Tory-ish) — and various opposition groups — the Proles, the Plebs and the Workers’ Party, whose rally gets bombed, sparking riots and crackdowns.

The complicity of the ruling class in this and a subsequent atrocity that returns them to power is a powerful indictment of the country, but Kuhnberg hurriedly returns to Riddle's hunt for his father.

A confusingly scripted car journey with various unsavoury companions ends with Riddle encountering his father. He assumes he's his brother, although the reader knows better.

The fate of this society’s women and girls is hinted at but only as an afterthought, leaving the reader none the wiser. All that remains are a few incomplete appendices.

Perhaps that’s the point. Maybe the author is deceiving us as well as his characters, but to be properly taken in a reader must want to be so and thus willing to suspend disbelief.

I didn’t — I was simply frustrated at how a much better book was lying around somewhere in this unruly jumble.