This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

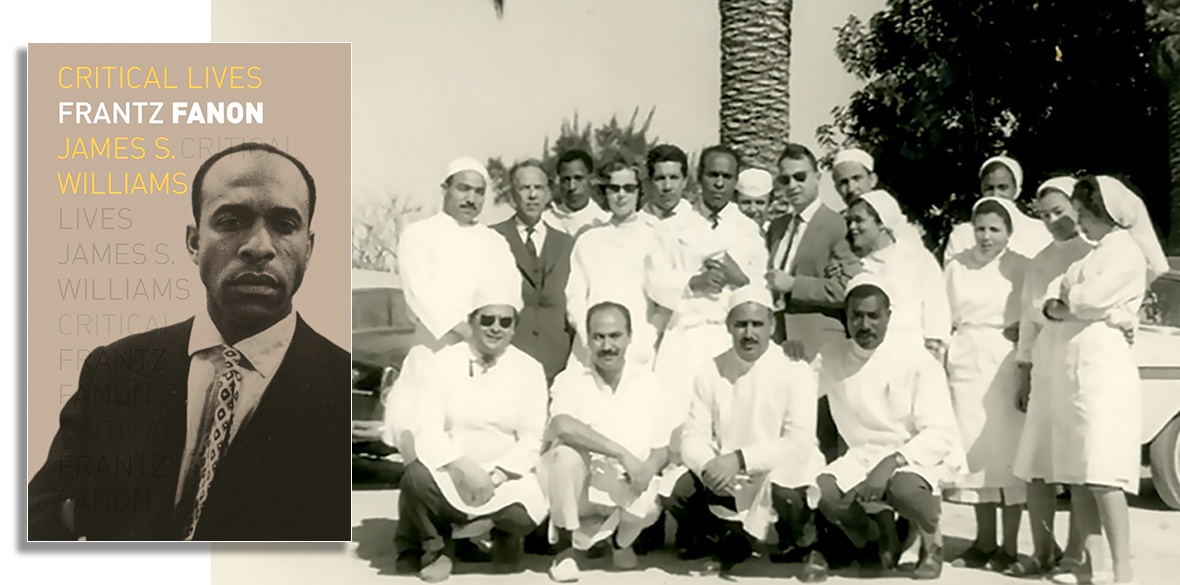

Frantz Fanon

by James S Williams, Reaktion Books £12.99

FRANTZ FANON (1925-1961) was a phenomenon, as this new biography sets out to explain.

In his short life (cut off by leukaemia at the age of 36) Fanon had been a soldier, fighting fascism in the second world war, a militant in North Africa during the Algerian war of Independence (1954-1962), an innovative psychiatrist, an ambassador, a journalist, a pan-Africanist internationalist and one of the most influential thinkers on anti-colonialism of his time.

Growing up in colonial Martinique, Fanon imbibed the assumption that French education would enable black students from the colonies, like himself, to become assimilated – and to think of themselves as being culturally white. He was only to discover the reality of racism when he reached France and experienced this for himself.

After the war he studied medicine in France, as well as taking courses in literature and philosophy. Marxism was a significant influence, although he was by no means a conventional Marxist, and he was deeply sceptical about the French Communist Party’s lack of support in the struggle for Algerian independence.

This was the struggle that he himself joined when working in Algeria’s only psychiatric hospital, treating French torturers by day whilst clandestinely treating Algerian victims by night.

He and his family left Algeria just in time, before the authorities caught up with his double life, going into exile in Tunisia in 1956. From there he continued to support the Algerian struggle as a spokesperson and writer, getting involved in the Pan-African movement as well as continuing to practise as a psychiatrist.

Williams outlines Fanon’s original contributions to psychiatry, exploring the social causes of mental illness in the colonial context. As Fanon wrote in his first major publication, Black Skin, White Masks, the spread of European “civilisation” was responsible for colonial racism, propagating corrosive stereotypes which the colonised could come to internalise, suffering from inferiority complexes precisely because of the colonisers’ assumed superiority.

Drawing on these insights, Fanon developed innovative approaches to treating the victims of colonialism. But the underlying causes needed to be tackled head on, in his view, through the armed struggle.

Fanon developed his thinking about the processes of decolonisation in his final book, The Wretched of the Earth. The draft was written in about 10 weeks – a race against time given the precarious state of his health by then. No wonder then that the book contains some sweeping generalisations and polemical denunciations of colonialism, Williams comments, rather than providing a more closely referenced account. Rather, The Wretched of the Earth makes an impassioned case for freedom from colonialism, setting out a vision of total emancipation for the future.

Fanon was only too aware of the risks involved, recognising the potential threats that an opportunistic national bourgeoisie might pose, seeking to take over from the departing French. The Wretched of the Earth includes significant insights into such challenges for postcolonial societies.

Aspects of The Wretched of the Earth have been deeply controversial on the left, however.

Fanon emphasised the revolutionary roles that could be played by the most disadvantaged in society – the “wretched” of the book’s title, who had the least to lose and the most to gain from colonial freedom, counterposing them against the working class whom he described as having been relatively “pampered.” This was hardly a conventional Marxist analysis, nor was it based upon a precise analysis of class divisions in the Algerian context.

Neither was his emphasis on the purifying effects of violent struggle, an emphasis which was amplified by Jean-Paul Sartre in his controversial introduction. Williams suggests that Fanon’s own views on violence were actually far more nuanced than Sartre’s however, quoting Fanon’s reflections on his natural repulsion for bloodletting which he attributed to his own position in society, as an intellectual.

Fanon has been much criticised on the left, then. But he has also been a significant influence on those involved in struggles against colonialism and racism, across continents.

The final chapter lists those who have acknowledged their debts to Fanon’s thinking from Steve Biko, leader in the South African struggle against apartheid, to Stokely Carmichael, Black Power leader in the US who (wrongly) claimed Fanon as a black nationalist (which he wasn’t).

Despite its shortcomings, which Williams acknowledges, The Wretched of the Earth has been an inspiration to many activists, both past and present. His understanding of decolonisation as a process has continuing relevance in the contemporary context, still marked by colonialism’s toxic legacies, along with his emphasis on the importance of political education and the development of critical consciousness in the struggle for transformative change.

Williams’s biography recognises Fanon’s shortcomings, including his personal shortcomings, as well as appreciating his extraordinary achievements. Morning Star readers may be more interested in Fanon’s ideas than in Williams’s discussion of the details of his personal life and career – although these details do have relevance, illustrating the ways in which his understanding of racism and its insidious effects were shaped, along with his thinking on transformative change.

This book is, in other words, an encouragement to read Fanon for ourselves.