This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

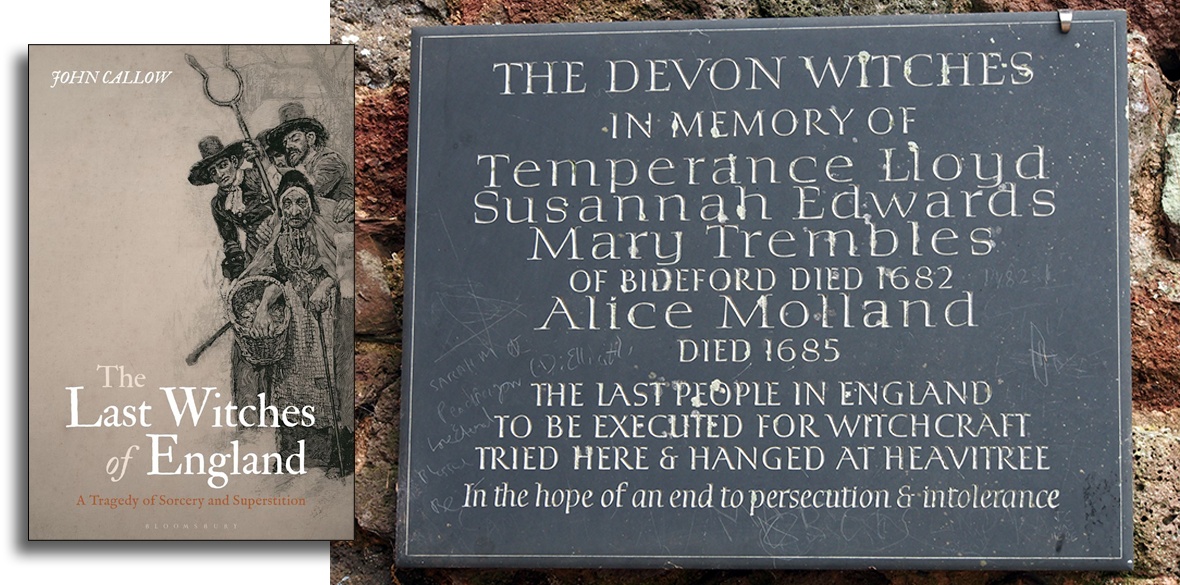

John Callow

The Last Witches of England: a Tragedy of Sorcery and Superstition,

Bloomsbury Academic £25

THERE seems to be a rash of publications relating to witchcraft and witch-hunting at present, due to the situation in current politics.

When an accusation, alone, can be held to be proof of guilt, then witch hunting must seem to be a reasonable analogy.

The poor, and especially poor women are generally invisible to history. Often judicial records are the only sources where they appear, beyond the bare facts of their baptism, marriage and death.

Although often “interpreted” by the rich and powerful, they remain one of the few windows into the lives of the poor.

Using these sources Callow has produced a work of social history. Unlike in much “cultural history,” here the economic base upon which the cultural, political, religious and legal superstructure sits is very clearly described and explained.

Even the conservative BBC History Magazine has published a glowing review of a book that has a story of class and class conflict marbled through its account of Temperance Lloyd, Susanna Edwards and Mary Trembles, their lives of wretched poverty, their prosecution, trial, conviction and hanging for witchcraft.

Callow shows that in prosperous, urban, cosmopolitan Bideford, the ties of class trumped differences of party and religious affiliation and illustrates how statements could be manipulated to “prove” pacts with the devil and other practices.

Although the Royal Society can be cited as evidence of the “rationalism” of the second half of the 17th century, it is worth remembering that Isaac Newton also practised alchemy.

The Stuart kings believed in the “royal touch” — a “curative” practice of laying hands on those afflicted by the “King’s Evil” (a tuberculous swelling of the lymph glands).

Many of the modernising, rational reforms of the Commonwealth were rolled back at the Restoration and were not resumed until after the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

This is the political and ideological context in which Sir John Holt, sitting at the Exeter Assizes in 1696, showed not only disbelief in spectral evidence but also in the ability of witches to use magic to do harm.

Holt could not have said such things from the bench before 1688. Perhaps this is to be the subject of a subsequent work.

A clearer explanation, in chapter eight, of the differing roles and make-up of Grand Juries, responsible for the indictment of the accused and mostly composed of “gentlemen,” and the Petty Juries made up mostly of “middling men,” which sat at the trial and gave the verdict, might have been helpful when discussing the political manipulation of jury selection.

If you are looking for an elegantly presented, well illustrated and readable book on how class conflict played out through witch hunting, this tome is for you.