This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

The Spaces Between: Richard Welsby

Pier Arts Centre, Stromness, Orkney

AT the centre of Richard Welsby’s work lies a unique account of art in the service of a humanitarian mission in the aftermath of war.

The words are simple, honest and direct. They describe the days and the people encountered during an independent film project in Bosnia in 1997, that accompanied a returning refugee and her need to find both her missing husband, and to grieve, and to begin life again. It was a brief but significant intervention that crossed the paths of several witnesses, and led to a forbidden place: a dank cellar beneath a camp that had formerly been a school.

There are two sets of images from this experience, both black and white.

In one, Welsby documents the objects and encounters in a series of elegant and telling images — prisoners’ home-made playing cards, the rooms and toilets of the vacant, abandoned camp, and the dreadful cellar with an inscription in Serbo-Croat on its wall: “Whoever survives this lives 100 years.” Many of these images can be found in the eventual film, The Ring.

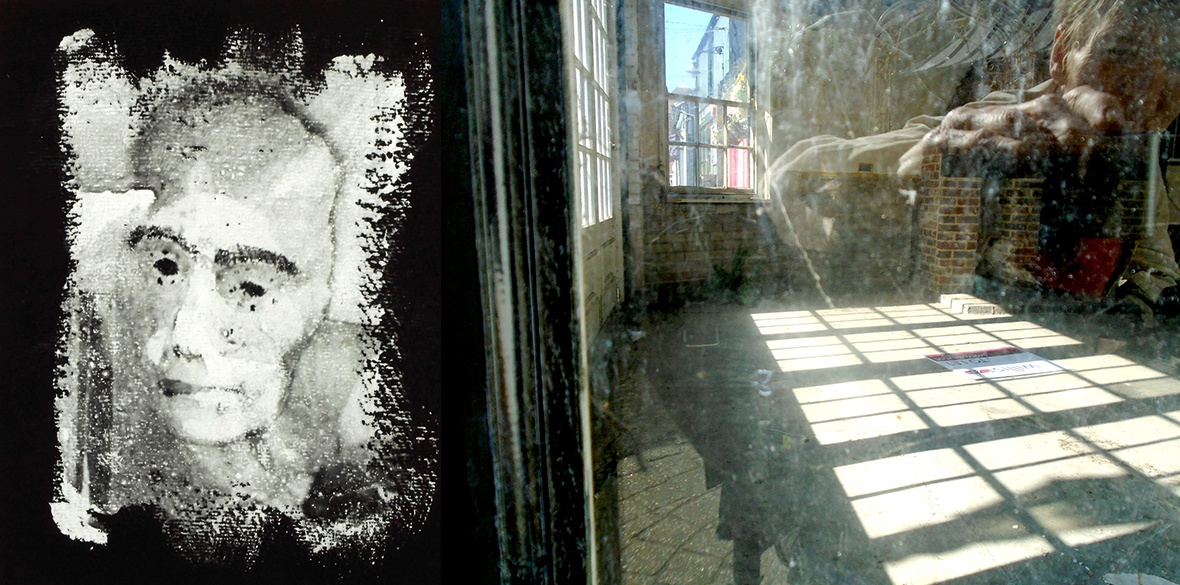

In the other, which form part of the current retrospective of Welsby’s work at Pier Arts Centre in Stromness, Orkney, are photographic images that do something else entirely: they demonstrate in figurative terms what the face of a damaged soul looks like. They could be snapshots taken by Dante on his journey through the Inferno. They are hard to look at.

These images are mostly printed on black paper painted roughly with white and then brushed with photographic emulsion, in a unique and painterly way to treat the photographic image that Welsby mastered, and made his own.

The method alters the status of the photographic image in both obvious and subtle ways. First, and obviously, it makes the print a singular event that cannot be duplicated. Thereafter, the singular image can escape the banality of mechanical reproduction to assert its own relationship to art, and the history of art, as well as the specific time and place from which it draws its existence.

This meditative way to use a documentary medium is unprecedented in contemporary photography. They testify as a clear-eyed if horrified witness to damage done in the contemporary world. This is the damage done to the relationship between people, to what the show describes as Welsby’s attention to ”the spaces between.”

Like everything in Welsby’s work they have the flavour of discovery and chance, as well as that of images that are the result of a profoundly introspective process, and they reward attention. The human face is presented as a mask that has an air of weariness and unchangeability — a mask that has become inseparable from being itself. These faces could be those of a god, or a child, or a bureaucrat, or a Stoic, but they all seem determined by the attrition of war and mutual alienation.

And they contrast, in the work of this remarkable and ultra-sensitive artist, with his own vision of paradise: the delicate celebration of natural forms that make up another series produced in a similar way: “The Garden of Earthly Delights.”

Here the emulsion is painted onto white cartridge paper and the resulting prints have both the delicate delineation of natural form, like a sketch in graphite, and the precise line and depth of field that could only be photographic. For a precedent you must look back to the meticulous fascination with ordinary nature that you find in the north European Renaissance, and images like Durer’s Great Tuft Of Grass, 1503.

This artist, in other words, is able to capture and transmit his lived experience of both Heaven and Hell, horror and joy, Innocence and Experience, and we never doubt the authenticity of his statements.

The images may look instant and lucky, but the path by which Welsby came to perfect this practise required a life-long and disciplined interrogation of form. His early work and his film-making are characterised by rigorously structuralist processes that are scrupulously impersonal. The meaning is always deferred through multiple surfaces in a kind of “serial music for the eye,” as though John Cage had chosen to compose with Bolex, multiple mattes and London in the 1970s, in a gentle deconstruction of the ordinary.

What is revealed by this retrospective is that the self-imposed limitations of Welsby’s practise served to achieve something transcendent. His work may be founded in the non-subjective demonstration of a process but it develops into singular images that, even in their delicacy, are monumental and objective, and a deeply humanistic celebration and critique of our time and its zeitgeist.

This development marks Richard out from his better known brother, the doyen of British experimental film-making, Chris Welsby. Chris is the master of process; Richard is the master of image.

So — who was he?

In 1994 he was invited to contribute a self-portrait to a group show in Orkney and the experiment emphasises the conflict in Welsby’s work between process and image. He says: “I decided to use a photograph taken without my knowledge and therefore without any personal self-consciousness involved. This freed me to work personally with my photographic treatment…” So far so orthodox in adherence to structuralist method, and the resulting image is a series of rubbings out and a kind of erasure of the self.

But when Welsby himself was “erased” by a stroke in 2008 that paralysed his “useful” right side, this ineradicable and persistently creative artist produced a series of altogether more remarkable self-portraits that riff on his familiar themes of transience and texture, reflection and shadow, using a cheap digital camera with his left hand to capture himself in the act of creation.

Once again, these images are very modest but nevertheless extraordinary achievements that both portray his disability and surpass it. They are not just a benchmark in disabled art but a portrait of the contemporary artist as marginal but unapologetic; as curious, playful and insistent: a real embodied presence in a world that we share. They seem joyful.

Welsby died in 2022, and throughout his life supported himself and his family with commercial photography, living a modest and marginal existence. His photographic archive of Orkney — a comprehensive historic, environmental, social and cultural record — has been gifted to Orkney Library and Archives. This retrospective, curated by Clare Froy, offers an overview of his development as an artist in parallel to that existence.

A labour of love, it presents iconic works that reward serious attention and deserve wide recognition both for the way that they demonstrate new avenues in British art, and the human insights they deliver.

Runs until June 8. For more information see: pierartscentre.com.