This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

IT IS widely understood that the very powerful forces of climate change denial have delayed action to address the climate crisis and thus are responsible for a huge amount of suffering and deaths attributable to climate breakdown.

Less appreciated is the unintended impact these dark corporate interests have had on the popular perception of climate experts. For example, having only recently started to move beyond framing the debate as being between denialists and those who accept the scientific consensus, the media largely present climate experts as one big monolithic block. Rarely do they explore the different politics that exist amongst the climate community.

This is deeply unhelpful, because the politics of individual climate specialists and research institutions have huge ramifications in terms of discussing the climate crisis, about who or what is to blame and therefore what action needs to be taken and when.

To explore this, it is worth comparing opposing voices on key climate issues: Professor Kevin Anderson, chair of Energy and Climate Change at the University of Manchester and two key figures at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment (GRI) at the London School of Economics — co-director Lord Nicholas Stern and policy and communications director Bob Ward, both of whom regularly appear in the media.

First, how do they engage with Naomi Klein’s argument in her 2014 book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs The Climate that stopping the worst effects of climate change will involve “challenging the fundamental logic of deregulated capitalism” and that systematic and radical change is required as soon as possible?

Stern, second permanent secretary at the Treasury under Gordon Brown and author of an influential 2006 report on the economics of climate change, does not generally frame the climate crisis like Klein. Instead, in 2015 he noted that “economic growth and climate responsibility can come together and, indeed” are a “complementarity.”

Indeed, in 2019 Julia Steinberger, Professor of Societal Challenges of Climate Change at the University of Lausanne, tweeted about “Lord Stern’s admonition to researchers in sustainable prosperity at the British Academy to maintain growth-at-all-costs back in 2014.”

Six years later Stern was backing “green growth” as “essential for our future on this planet” (one of the five founding research programmes of the GRI, widely seen to be dominated by economists, was “green growth”).

In contrast Anderson argued in 2013 that “the remaining 2°C budget demands revolutionary change to the political and economic hegemony.” In addition, he noted “continuing with economic growth over the coming two decades is incompatible with meeting our international obligations on climate change” and therefore wealthy nations needed “temporarily, to adopt a de-growth strategy.”

Anderson is dismissive of the concept of “green growth,” tweeting in 2019 a link to an interview with Johan Rockstrom in which the internationally recognised scientist says “green growth is wishful thinking.”

To be clear, in recent years Stern seems to have become increasingly aware of the scale of the change required, noting in October 2021 that achieving net zero emissions “will require the biggest economic transformation ever seen in peacetime” (though he still seems wedded to the ideology of economic growth).

When it comes to fracking, in 2014 Anderson told the New Scientist “The advent of shale gas is definitely incompatible with Britain’s stated pledge to help restrict global warming to 2°C.” However, the article noted “others say it could help reduce emissions overall, provided the shale gas replaces coal currently used to generate energy,” quoting Ward as saying “In principle, if it helps with displacement of coal it could be helpful.”

In May 2019 Theresa May’s Tory government announced Britain would aim for net zero emissions by 2050. Stern stated at the time “This is a historic move by the UK government and an act of true international leadership for which the Prime Minister deserves great credit.” Since then Stern has led on the LSE itself also adopting a net zero target of 2050.

Anderson was less enamoured by the 2050 target, noting on his blog that “to meet its Paris [Agreement] obligations the UK must achieve zero-carbon energy by around 2035; that’s ‘real-zero’ not ‘net-zero’. This requires an immediate programme of deep cuts in energy emissions rising rapidly to over 10 per cent per annum.”

In October 2021 the British government published its strategy for reaching net zero emissions by 2050. Anderson’s response recorded by the Science Media Centre? “The UK’s net zero strategy falls far short of both its Paris [Agreement] and G7 temperature and equity commitments.

“Scour the associated spreadsheets and the numbers reveal a story of subterfuge, delusion, offsetting and piecemeal policies.” In contrast both Stern and Ward were broadly supportive, with the former telling the Science Media Centre “I welcome the publication of the strategy, which identifies the major steps we have to take to reach net zero.”

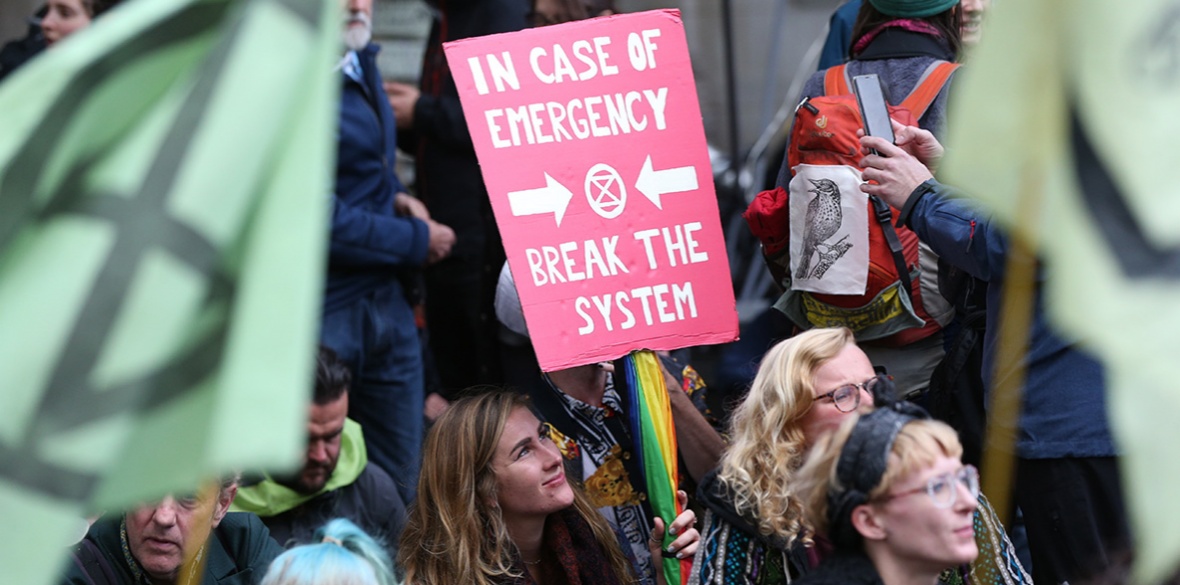

Finally, there is a consensus amongst many prominent activists and experts that strong grassroots social movements will be required to force the radical changes needed to address the climate crisis.

Anderson seems to understand this. I’m aware he lent his expertise to anti-airport expansion group Plane Stupid in the 2000s and, more recently, he has explained he advised youth strike figurehead Greta Thunberg. In 2020 he gave a talk to an Extinction Rebellion group in Waltham Forest.

In contrast, Stern and Ward’s leading role in setting a 2050 net zero emissions target at LSE was undertaken in the face of grassroots opposition from LSE students and staff, with a petition signed by hundreds of people calling for LSE to adopt an earlier net zero target of 2030.

As far as I am aware Stern and Ward refused to seriously engage with this grassroots activism (in 2019 a small group of staff met with Ward and argued there need to be more radical action on reducing emissions at LSE, including the declaration of a climate emergency, receiving a very frosty reception, to put it mildly).

It seems telling that Channel 4 News decided to put Ward up against Extinction Rebellion’s Farhana Yamin during a 2019 studio discussion about the 2050 net zero target, while the Mail quoted Ward in a 2021 article to criticise a statement Thunberg made about the British government’s response to the climate crisis.

From this very brief summary, it seems clear Stern and Ward are, broadly, conservative actors amongst climate experts when it comes to the climate crisis.

“The voice of experts on climate science is an important one, because citizens trust it. And some climate scientists have been using their voice powerfully and well, especially in recent years,” academic and environmental campaigner Professor Rupert Read tells me.

“But it’s important to remember the limits of the expertise of most climate scientists: to their own discipline or even sub-discipline. Few are experts in systems theory, in risk analysis, in philosophy, or in political economy. For expertise in those areas, funnily enough, you are best off going to experts… in those areas.”

Read notes “economists — whose opinions are often over-valued in an economistic society such as ours — who weigh into debates originating in climate tend to lean towards technocracy and tend to be biased in favour of growthism, which is even now, incredibly, an endemic assumption in economics.”

“Thus degrowth, post-growth, deep green ecological economics — let alone approaches based in civil disobedience or coming from (say) indigenous or eco-spiritual perspectives — tend to get short shrift from climate economists. That is a problem. A big problem.”

All this shouldn’t be surprising when you consider Stern’s and Ward’s successful professional careers are tied up with elite networks, establishment politics and billionaire investor Jeremy Grantham.

Of course, a variety of voices is welcome but, to echo Read, it’s surely a serious problem worthy of serious discussion when the climate crisis demands radical action and Stern and Ward have so much power within the climate community and cachet with journalists and therefore an oversized impact on the national debate and research agenda.

Indeed, their commanding positions likely have a chilling effect on the kind of robust debate scientific and political progress thrives upon. If you were a young climate researcher, would you risk access to funding, contacts and therefore your future career by criticising two of the most powerful people in your field, or the leading institution they run?

For the wellbeing of everyone and everything that lives on the planet today and in the future, we need to start talking about the politics of climate experts and climate-focused research institutions.

Follow Ian on Twitter @IanJSinclair.