This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

MANY readers of the Morning Star will know by heart the words of Alfred Hayes’s most famous poem, although they could be more familiar with it as set to music by Earl Robinson and as song by left luminaries like Pete Seeger, Paul Robeson or Joan Baez.

That great celebration of the state-murdered IWW activist, I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night, was originally a poem by Hayes.

Hayes was born in Whitechapel on April 11 1911 to working-class, left-wing Jewish family who moved to New York when he was three.

As a young man he was a member of the Young Communist League for a short while and worked in many blue-collar jobs.

He was already writing poems and some of them found a home in left-wing publications like the New Masses and the Partisan Review.

More comfortable with working-class people, he was described at this time by historian Alan Wald in his work on New York intellectuals, to be the “Byron of the poolhalls.”

According to Vivian Gornick, he maintained this brooding, darkly intense Marxism and his awareness of the class struggle all his life.

On landing a job as crime reporter on one of the New York tabloids, he developed the skills that would produce at least a dozen screenplays and seven novels.

His wartime service saw him in Italy and his experiences in allied-occupied Rome provided the backdrop of his first novels.

All Thy Conquests (1947) is set over one day in September 1944, the day of the trial of fascist Pietro Caruso, head of the Italian police during the final part of the war.

Together with the German Gestapo chief Hebert Kappler, he had organised the Fosse Ardeatine massacre of 355 people many belonging to a communist resistance group.

Caruso was sentenced to be shot in the back. Scenes of his execution were captured by British Pathe news.

Hayes became a screenwriter in that wonderful post-war blossoming of realist Italian cinema.

After the success of his film Rome Open City, Roberto Rossellini produced an episodic film, Paisan (1946), covering the end of the war in Italy from the allied invasion.

Hayes worked with Roberto Rossellini on Paisan during the months after Italy surrendered and before he shipped home to New York in December of 1945.

Having kept the story rights, he wrote All Thy Conquests after returning home.

His other work at this time included uncredited writing on Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948), ranked at the time as the greatest film ever made by Sight & Sound.

Hayes then made his way to Hollywood, gaining writing credits on The Lusty Men (1952), directed by Nicolas Ray, and the film adaption of the Maxwell Anderson/Kurt Weill musical Lost in the Stars (1974), an adaption of an adaption being originally based on Alan Paton’s novel, Cry, The Beloved Country.

In between he worked on numerous TV series, including Alfred Hitchcock Presents, the Twilight Zone, Nero Wolfe and Mannix — everyone must make a living after all.

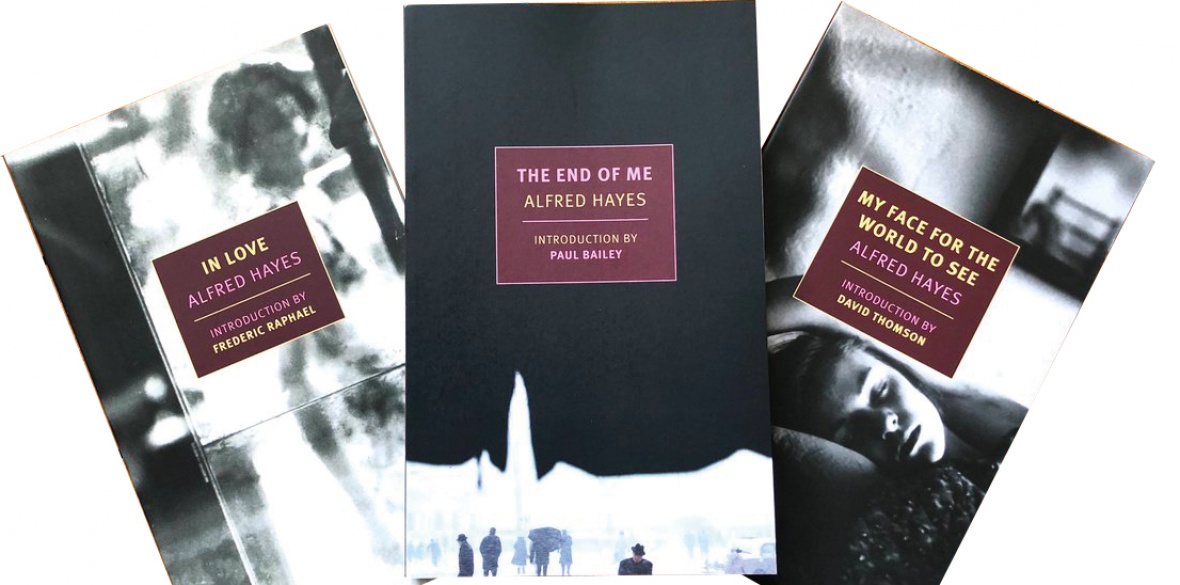

Today, however, Hayes is best remembered for his trilogy of novels informed by his time as a screenwriter, In Love (1958), My Face for the World to See (1958) and the End of Me (1968).

These books have been beautifully republished by the New York Review of Books with introductions by Frederic Raphael, David Thomson and Paul Bailey consecutively.

Despite being a mid-level studio hack, his time in Hollywood was not wasted as it gave him the experience and language for these short but mesmerising novels.

They tell the story of the shallowness and emptiness of the Hollywood dream. He articulates how alienation poisons personal relationships and how even success is just another kind of failure.

In My Face in the World he has the narrator explain: “There was something finally ludicrous, finally unimpressive about even the people who had all the things so coveted by all the people who did not have them.”

What’s more, he says, “There was something sinister about the way these people lived.”

Gornick, author of the Romance of American Communism (1977), points out in her review of these novels that it “struck Hayes forcibly that the Hollywood obsession with making it was responsible for some of the most soul-destroying behaviour humanity was capable of.

“If you were successful you could and did inflict horrifying humiliations on those who where not: if you were on the outside wanting in, you were capable of prostituting yourself to an equally degrading extent.”

As Hayes himself put it, “The town was full of people lying in bed thinking with an intense, an inexhaustible and almost raging passion of becoming famous if they weren’t already famous and even more famous if they were; or of becoming wealthy if they weren’t already wealthy or wealthier if they were.”

Hayes died in 1985. These novels exposing the dark underbelly of contemporary celebrity are his greatest legacy.